On 17 August 1915 a letter sent to his mother from a West Coast soldier was published in the Greymouth Evening Star. He was a trooper with New Zealand’s main Expeditionary Force serving in the Dardanelles in 1915, the second year of World War One.

The writer, Private Herbert John Muir, was from Three Mile, located on the outskirts of the town of Hokitika on the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand. The publication of the letter was of local interest as Private Muir was not the only local lad to be based in the Dardanelles. He mentions four others, including Charles Keogan, aged 27 in 1915 and my paternal great-granduncle. It placed Charles in the Gallipoli Campaign, a battle infamous to New Zealanders and Australians. It also mentioned Charles’ job in that campaign. Herbert wrote that ‘Charlie Keogan is in the bomb-throwing gang. They have a dangerous job’. At the end of the letter he claimed that ‘Charlie is still going strong’.

The day after the letter was published, Charles was not going strong anymore – due to injury from a bomb – and four days after that, neither was Private Muir. However, they did come home – they were two of the fortunate in that respect.

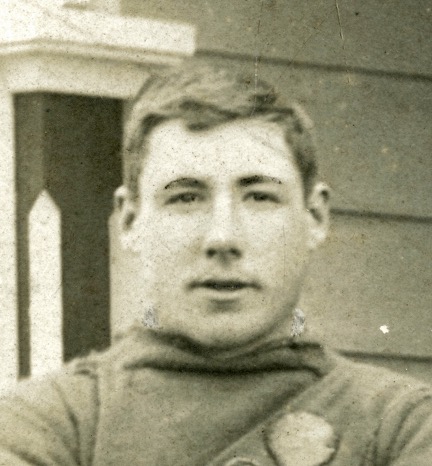

Charles Keogan

Charles was born in 1888, although on his enlistment his year of birth is recorded as 1889. He was the fourth child of Catholic Irish immigrants. His father, John Keogan was born in Martinstown, Athboy in County Meath. He too had been a soldier, albeit I suspect, having survived the Great Hunger, his reasons for enlisting were not the same as those of his son. Charles’ mother, Margaret Donohoe, was born near Ballyconnell in County Cavan.

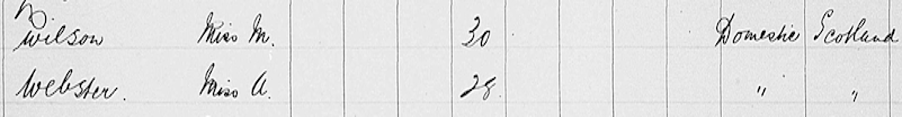

Charles enlisted in the Canterbury Infantry Battalion (13th North Canterbury and Westland) at Hokitika. His address was Three Mile and his employer was J. C. Malfroy & Co., timber merchants in Hokitika. He is recorded as a sawmill hand, although the electoral roll records have his occupation as bushman. Enlistment records gave a description of Charles. He was single, aged 25 (two years younger than he was), with a thirty-six inch chest and weighed one hundred and fifty-three pounds. Charles was five foot six inches tall with a dark complexion, brown eyes, dark hair and sound teeth. He was a Roman Catholic. By all accounts, he was strong and healthy.

The New Zealand contribution to the war effort

The name given to the force Charles joined was the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. In August of 1914, the New Zealand Government offered Britain a division of two brigades – one mounted and one infantry. On acceptance of the offer, the infantry brigade started recruiting on a territorial basis. Two battalions, with four regiments each, were sent from each island, the North and the South. Each brigade included a field ambulance, and engineer and supply companies. The regiments were numbered and, to foster local pride, regional. For Charles, this meant recruitment to the 13th North Canterbury and Westland Regiment, one of four in the Canterbury Battalion.

New Zealand Battalions

Auckland Battalion

3rd (Auckland), 6th (Hauraki), 15th (North Auckland), and 16th (Waikato) Regiments.

Wellington Battalion

7th (Wellington West Coast), 9th (Hawke’s Bay), 11th (Taranaki), and 17th (Ruahine) Regiments.

Canterbury Battalion

1st (Canterbury), 2nd (South Canterbury), 12th (Nelson), and 13th (North Canterbury and Westland) Regiments.

Otago Battalion

4th (Otago), 8th (Southland), 10th (North Otago), and 14th (South Otago) Regiments.[1]

Training and Transport

Charles arrived, with other Westland recruits, at Addington Show Grounds in Christchurch on 15 August 1914, one day after Britain accepted New Zealand assistance in the war effort. Once they arrived, each regiment was divided into four platoons commanded by a subaltern.[2]

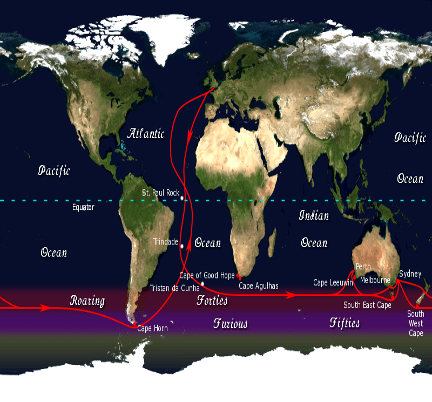

The Canterbury Battalion remained in and around Christchurch for training until finally embarking at Lyttleton Harbor on 23 September 1914. The 13th Company, including Charles, was on the ship Athenic, along with the 2nd, and 12th companies. Accompanied by the Tahiti, transporting the 1st Company, the machine gun section and sixty horses they finally left Lyttleton on 2 October 1914, joining the Otago transports for Wellington. The plan to join with the North Island transports and leave immediately was subverted due to increasing naval risks in the South Pacific.

While waiting for a naval escort to arrive the ships berthed in Wellington and the troops were taken ashore daily for training in the hills and rifle practice at Trentham. They eventually left New Zealand on 16 October 1914 after the arrival of an escort and the Auckland transports. A letter published from a diary sent home by another West Coaster, Private Robert Charles Ecclesfield, describes his thoughts on leaving Wellington.

“All on board were in the best of spirits and with a glorious day and the sea like a mill pond surely fortune was smiling on us in every way. That day will linger long in my memory, and will not every man of us remember that day.”[3]

The next morning he was not so sanguine. He described angry lashing seas and bunks that were rising and falling in a mysterious manner.

“Led, by habit; I went to the breakfast table. One mouthful of stew and I stopped to think; my thoughts gave way to imagination; the imagination! became real; and I hurried on deck and joined in a putting competition which was going on over the side until the bugle sounded the fall in. During the parade the words: “excuse me sergeant l am wanted at the side,” helped to make the parade bearable, at times even humorous!.”[4]

The first stop for the New Zealand contingent was Hobart on the island of Tasmania in Australia. The troops went ashore for a march that unfortunately resulted in a six-hour pack drill once back on board. Their misdemeanour? ‘participating in the hospitality of the citizens of Hobart’.

Apples had been scattered among the soldiers who with

“eager hands groped on the ground and shot in the air in their endeavour to secure these delicacies. For this action we were to pay dearly…and… we partook of those delicious golden apples in fancy only, thereby adding another page to our book of discipline.”[5]

The convoy sailed, finally calling at Albany, approximately 420 kilometres east of Perth, in Western Australia to join the Australian convoy. A combined fleet of thirty-eight Australian and ten New Zealand transports thereby sailed for England.

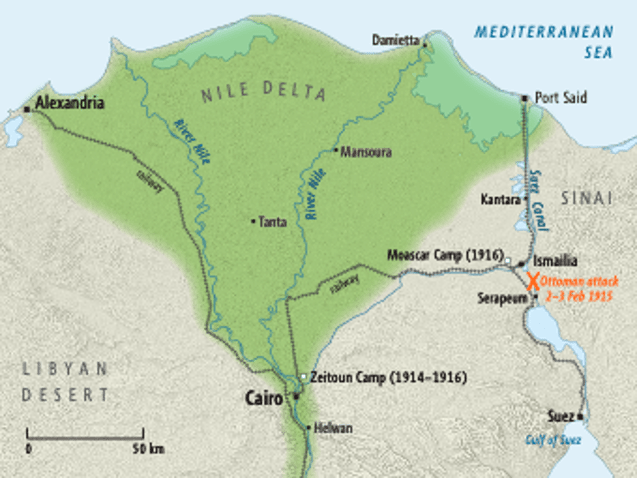

The Athenic, carrying Charles, was one of the faster ships, and they called at Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) on 15 November 1914 to take on board coal and water. Their final stopover was Aden (now in Yemen) for one day. At this time that the convoy was redirected from their original route to Europe to Alexandria in Egypt to complete their training after the Ottoman Empire allied itself to the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. They finally arrived on 3 December 1914. The New Zealand force was ordered to Zeitoun, four miles northeast of Cairo. They were joined by the British three weeks later.

Zeitoun, Cairo, Egypt

A correspondent with the New Zealand Forces described several aspects of life in the four or so months the battalions spent in Zeitoun and its immediate surrounds. Along with other published letters in New Zealand newspapers, it is possible to get a glimpse of what life was like for Charles in those months. On arrival in Alexandria, the soldiers travelled by train to the camp. No accommodations had been prepared and the first night was without shelter. The cold of a desert at night was unexpected and many stayed up with constant transports of men and equipment arriving.

The camp itself was within half a mile of the train to Cairo. It ran every thirty minutes and the tram service to Heliopolis was also close. With soldiers earning fourteen shillings per week and half-price fares provided on all Government lines, regular trips into Cairo were possible. The men were housed in bell tents. Trading licenses granted to Egyptian vendors to supply camp occupants saw men able to purchase goods “without leaving his tent”. The camp became a mini town with the usual facilities springing up, including fruit stalls, barber shops, tailors, picture shows, chemists, and restaurants. In addition, the Y.M.C.A. and Salvation Army provided marquees with weekly concerts, lectures and places to read and play games were provided.[6]

One young soldier from Oamaru who must have been in a mounted regiment wrote of sights in the first few days.

“We rode our horses for the first time to-day, and went a few miles through some native gardens, which are watered from a canal. We passed a party of Egyptian soldiers on white camels. There are lots of camels about and millions of donkeys”.

The bread baked for the troops came from ovens erected by Napoleon, and he could see the Pyramids from the camp. Officers were taking groups of their regiments to see them. He mentioned they marched eight miles through the “blooming desert” yesterday, to the rifle range.[7]

Novel fauna was detailed in a Wairarapa newspaper by a North Island trooper from Wellington who did not appreciate any of it. He described small wriggly eel like sand snakes around two feet long in the desert. Burrowing centipedes in tents made a noise and would jump ten feet in the air when disturbed by sleeping men’s feet who would inadvertently cause them to land on somebody. In addition, he was plagued by ‘a black bug with a sting half an inch long, which raises a lump on you about the size of a duck’s egg’ and a ‘hissing spider which hisses like a motor tire going down, is three inches across the back…stands about one inch high, and can run horribly quickly.’[9]

Training drills and downtime

Training consisted of drills, route marches through sand, activities such as skirmishing, bivouacking, trenching or artillery practice with live shells. The aim was to be capable of covering twenty-seven miles in a day.[10] With unlimited space, mounted regiments, infantry, artillery, machine gun sections, and field ambulances each had allotted grounds. The various units generally left camp at eight in the morning with their lunches after a 5.30 am wakeup call and returned at four in the afternoon. One correspondent for the New Zealand Herald wrote

“The parade ground was ‘open desert… stretch[ing] away into the haze”.[11]

Another wrote

“The result of this training is daily becoming more apparent, and it would be hard for the New Zealander at home to recognise in these hardy, well-trained looking men, the untrained recruits of a few months ago”.

The generals had stated that the progress of the troops would influence the date of their despatch to the front so that was possibly seen as motivation.[12]

Downtime and sport were part of the experience with Saturday afternoons free. Football matches between regiments were popular, as were running and obstacle course races. Donkeys were used for polo matches and mounted wrestling competitions.

New Zealand Forces attained the nickname “Massey’s Tourists’, named for the New Zealand Prime Minister of the time, William Massey. They had the time to explore Cairo’s new sounds, sights, smells, and tastes. Many visited museums, the Sphinx and pyramids, theatrical performances and Zoological Gardens and sent souvenirs home. By the time the force left for Gallipoli, four hundred and forty-five New Zealanders had been treated for venereal disease in a hospital set up for the purpose of treatment by the Australians.[13] The authorities had attempted to quell the desire for entertainments in Cairo by implementing a 10.30 pm curfew and setting up their own recreational facilities and canteens. The New Zealand Herald Correspondent went into some detail about the exploits of the Expeditionary Force in Cairo. He wrote that in the evenings

“the city is thronged with men in khaki…dash[ing] around in carriages, which are mercifully cheap, and hire[ing] donkeys, on which they scamper through the streets and have races, in spite of the loud protests of the native owners”.[14]

Christmas day was celebrated with a day off. Another Hokitika lad, Sergeant Harry Wild, wrote home about the Christmas Eve dinner provided for those from Hokitika with a portion of the money given by the Hokitika people for their young men. He wrote that it was ‘a very decent dinner, not at all beery like a report I saw sent about it would lead one to believe’. He mentioned the arrival of a New Zealand Contingent from London who mentioned that stores, sheds and accommodations had been built, and horse-lines prepared in England confirming that as the original plan for the New Zealand troops. He mentioned sleeping arrangements, with no straw, their hard beds had prepared them for future bivouacking.[15] Another writer commented that they slept on native rush mats.[16]

First engagement

On 25 January 1915 the brigade was considered fit enough to support an Indian Division defending the Suez Canal. With the Turkish advancing, the Canterbury Battalion went to Ismailia at Lake Timsah to become general reserves. They garrisoned posts at El Ferdan, Battery Post (both north-east of Ismailia), and Serapeum (south of Lake Timsah). One company was kept in reserve at Ismailia (Ferry Post) with a platoon of another company. The Turkish troops attacked on the third February.

The enemy attacked at El Ferdan, where the 13th Regiment Company and two platoons of the 1st Regiment Company were stationed. A Turkish Battery of four small guns opened fire on the Signal Station, hitting the buildings several times. The H.M.S. Clio arrived and silenced the batteries.

The shipping on Lake Timsah was subjected to shell fire during the day, along with the outskirts of Ismailia at various points. Though no regular attack was made, intermittent shelling continued. The New Zealand platoons actually saw no fighting, although they were exposed to shell fire throughout the day. Some of the shells fired at this point fell within half a mile of the ground where the Auckland and Canterbury Battalions were encamped. During the night of the 3rd a half-hearted attack was made, after which the enemy withdrew the bulk of their forces to Kataib El Kheil.

The event, for the British and their allies, was minor compared to what was to come. Although Charles and his colleagues stayed in the area until 26 February, most of the time was spent training. One Canterbury lad had found the ‘little sojourn to the front’ a more interesting event than the drills to date, even though they had missed any action. He wrote that everyone was sorry to be leaving the ‘pretty, little town of Ismailia with rumours regarding their next destination. He wrote that the First (Canterbury) Regiment had given a concert to raise funds for the Red Cross and Serbian refugees, which saw full attendance. He spoke of an epidemic of diarrhoea, some residents of Ismailia leaving for what they considered safer quarters and his amusement at the comments passed by some when reading sporting news from home, especially the cricket results, with some going down the lists and naming those who should be in Egypt, and who should not. That is, those with big scores would be assets. He stated

“We don’t get much money, but we do see life,” and the life is worth almost, any sacrifice”.

The author added to his letter on February 28 after returning to Zeitoun. He wrote that censorship was no longer a problem and mentioned Constantinople as a possible destination. With a sighting of H.M.S. Triumph passing through the Canal to bombard the Dardanelles,[17] he was closer in that summation than he probably knew.

After returning to Zeitoun, the field training increased with trench warfare, night assaults and entrenching practised. Battalions now were marching long distances daily with seventy-pound packs to prepare them for carrying the extra ammunition and rations for three days of self-sufficiency. Training intensity had increased with another writing to a friend in March 1915 saying:

“We have been having rather a trying time lately with a spell of unseasonable and very hot weather. We will be glad to get out of here. The heat has been accompanied by some awful sand storms, and it just so happened that while these were at their worst, we had some big field manoeuvres to practise – training on a huge scale. We do our training on the desert. This week we have been doing battle against a battalion of Lancashire Territorials, who are in camp near us. The whole of the New Zealand division goes out, and on Friday there were 30,000 men in the field. We don’t mind the walking, but when attack practices are on, and we have to double over the sand with our full packs on, it is a fair devil.”[18]

Mobilisation

An advanced base at Mustafa near Alexandra was established for a pending mobilisation. Infantry battalions of thirty-three officers and nine hundred and seventy-seven other ranks, along with additional reinforcements of one hundred per battalion were confirmed. The reinforcements and men not selected were to remain at Zeitoun, now designated a training depot.

The 12th and 13th Companies of the Canterbury Regiment left for Alexandria for Palais de Koubbeh Station on 9 April 1915. They embarked on theItonus later that day. The remaining companies in the regiments embarked two days later.

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps were one part of the Gallipoli campaign. Lieutenant General Sir W R Birdwood was in command. The Corps was made up of the Australian Division (1st, 2nd, and 3rd Infantry Brigades) and the New Zealand and Australian Division (the New Zealand Infantry Brigade and the 4th Australian Infantry Brigade). Although the latter included the New Zealand Mounted Rifles and 1st Australian Light Horse, these Brigades were left in Egypt as the attack was not suited to mounted troops.

The troop ships sailed to Mudros on the island of Lemnos where they waited for the plan of attack. Time was spent training onshore and practising landing drills. It was decided to land an Australian Division first to cover the disembarkation of following troops. The Australian transports sailed on 24 April. Fifteen hundred men of the 3rd Australian Division were transferred to smaller boats and towed to around two thousand metres off the landing site. The remaining twenty-five hundred troops were transferred to destroyers and towed to about the same distance. The position was about a mile north of that originally intended.

References

[1] The History of the Canterbury Regiment, N.Z.E.F. 1914-1919. Page 1-2. This format changed after the Gallipoli Campaign.

[2] Ibid page 71

[3] To Egypt. West Coast Times, 16 February 1915, Page 4. Accessed 25 October 2023 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WCT19150216.2.23?items_per_page=10&query=Private+Ecclesfield+diary&snippet=true

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Life in Egypt. Evening Post, Volume LXXXIX, Issue 63, 16 March 1915, Page 4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19150316.2.37?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=4&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[7] Letter From The Front. Oamaru Mail. Volume XL, Issue 12438, 2 February 1915, Page 3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OAM19150202.2.13?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=3&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[9] Reptiles in Egypt. Wairarapa Daily Times, Volume LXVIII, Issue 14232, 11 March 1915, Page 7 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WDT19150311.2.50?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=6&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[10] The History of the Canterbury Regiment, N.Z.E.F. 1914-1919. Page 1-2. This format changed after the Gallipoli Campaign. Page 12

[11] Work and Play. Press, Volume L1, Issue 15192, 2 February 1915, Page 8 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19150202.2.55.51?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=3&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[12] Life in Egypt. Evening Post, Volume LXXXIX, Issue 63, 16 March 1915, Page 4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19150316.2.37?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=4&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[13] ‘Massey’s Tourists’ – New Zealand’s Expeditionary Force in Egypt by Matthew Tonks – Web Advisor in the WW100 Programme Office. Accessed 25 October 2023. https://ww100.govt.nz/masseys-tourists-new-zealands-expeditionary-force-in-egypt

[14] Work and Play. Press, Volume L1, Issue 15192, 2 February 1915, Page 8https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19150202.2.55.51?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=3&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[15] Our Boys in Egypt . West Coast Times, 11 February 1915, Page 3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WCT19150211.2.20?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=2&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914&title=CHARG%2cGRA%2cGEST%2cHOG%2cIT%2cKUMAT%2cLTCBG%2cWCT%2cWEST

[16] Letter From The Front. Oamaru Mail. Volume XL, Issue 12438, 2 February 1915, Page 3 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/OAM19150202.2.13?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=3&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[17] Worth Almost Any Sacrifice. Press, Volume L1, Issue 15246, 7 April 1915, Page 7 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19150407.2.53.1?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=3&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914

[18] Training on the Desert. Press, Volume L1, Issue 15258, 21 April 1915, Page 10 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19150421.2.71.6?end_date=01-05-1915&items_per_page=10&page=3&query=Zeitoun&snippet=true&start_date=01-12-1914