The end of Thomas life seems to me to portray an everyday hard working family man. On tracing back, however, it seems he was ‘notorious’‘, ‘in the most daring gang to ever infest the neighbourhood’, and engaged in not so mysterious ‘doings’ in Dublin.

The earliest reference I found to Thomas was an article pertaining to his arrest. It stated that

McDonogh and Scott apprehended [the suspect]…coming out of Duignan’s public house in Mercer Street… found a large horse pistol… his own hat was subsequently found on the road at the scene of action. These fellows were soon recognised as two of a gang who made themselves notorious for their robberies within the last month… the pistolman the notorious Thomas Finla[y]n, who have very lately been spending seven months in Newgate for similar doings. He and his companion were committed till next Commission, which will sit at Kilmainham on the 9th of next month.[1]

Then I found this one…Thomas had been caught picking pockets in September 1832[2].

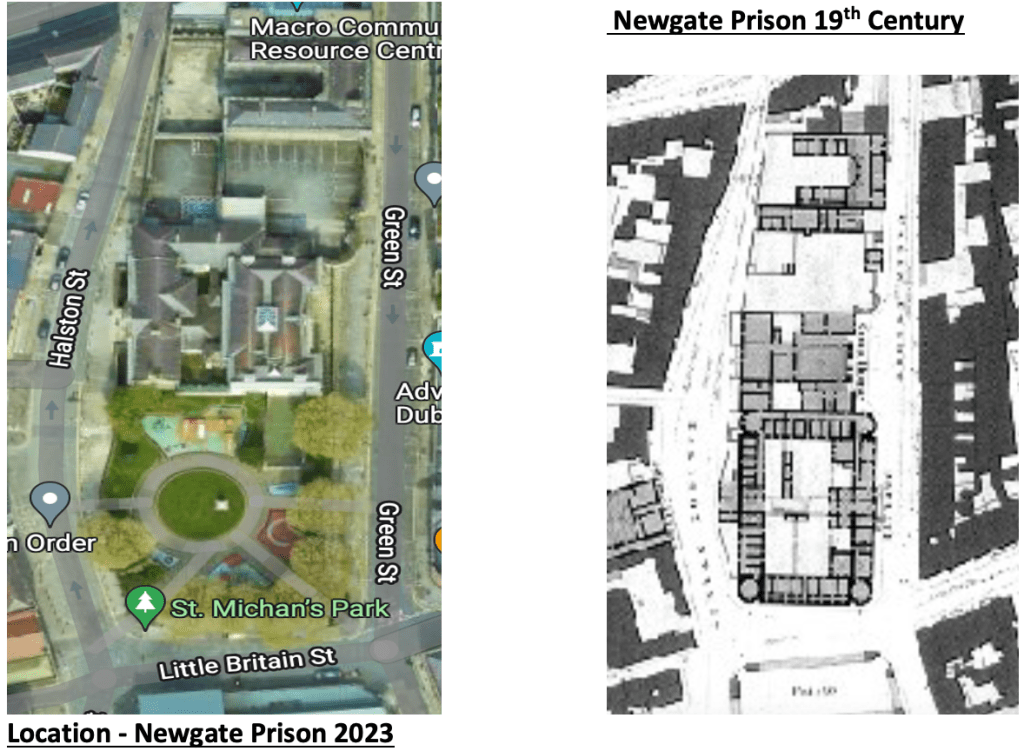

Newgate was one of two Dublin prisons he is known to have spent time in as well as a hulk before his transportation. When I first found this article I assumed it was talking about Newgate in London. I did not realise at the time that there was a prison of the same name in Dublin and that its location is about a five minute walk from where I now live. I wasted a lot of time looking at records relating to London’s Newgate and wondering why he was in that city. As it turned out he wasn’t there at all.

In 1835 an observation written about Newgate Prison in London was considered to be appropriate to Dublin’s Newgate Prison in that:

“There is a large public school, maintained at the expense of this city for the encouragement of profligacy and vice, and for providing a proper succession of house-breakers, profligates, and thieves. This school, too, is conducted without the smallest degree of partiality or favour; there being no man, however mean his circumstance, who may not easily procure admission. The moment any young person evinces the slightest propensity to these pursuits, he is provided with food and lodging, and put to his studies, under the most accomplished thieves and cut-throats the city can supply. There is not, to be sure, a formal arrangement of lectures, after the manner of our universities; but the stripling, committed for petty larceny, being left destitute of every species of employment, listens to their pleasant narrative of successful crimes, and pants for the hour of freedom, that he may begin the same bold and interesting career.”[3]

This was part of an article by the Howard Society who noted that executions where not the deterrent expected. They Society was calling for just and merciful principles in relation to punishment for crimes. John Howard, after whom the society (league) was named, believed in reform and rehabilitation through a regime of solitary confinement, religious instruction and hard labour.[4]

The Newgate Thomas had spent seven months in is the second Newgate in Dublin. The former was one of the old city gates in Cornmarket on the south side of the river Liffey and ‘small, inconvenient and in a ruinous state’. The new one was to provide ‘permanence, security, prevent the transmission of contagions and contribute to the convenience and comfort of its inmates.’[5] Consequently a sessions house opened in 1797, and sheriffs (built 1794)’ and debtors’ prisons where built in the area.[6] The prison did not live up to its promise.

The image above shows the outline of the prison (bottom of the image), sessions house and debtors prison (top of the image) in the nineteenth century with an image of how the location looks today.

The park is closed at present for remedial work so the photographs are not ideal I am afraid.

The foundation stone was laid on 28 October 1773 in Little Green on the north side of the Liffey. Warburton, Whitelaw and Walsh state that the site was “insufficient in extent to admit or has sufficient yards and other necessary accommodations for the different descriptions of prisoners….[and is] environed by dirty streets, and in so low a situation as to render the construction of proper sewers to carry off its filth impracticable[7].” The architect, Thomas Cooley, also built the record offices on Inns Quay, the Chapel in the Park, the Royal Exchange and the Hibernian Marine School[8]. Several complaints were ascribed to the building over the period of its use.

The site was bound on three sides by three streets; Green, Halston and Little Britain and on the fourth by the Sessions-house which meant the prison was unable to be enlarged. One side, adjacent to the Sessions-house meant ventilation on this side was limited and the walls, constructed of ‘small stones and bad mortar’ resulted in insufficient security according to critics.

Codes on Plan: AA – Four cells for Transports; BB – Six cells for Women; CC – Eight cells for Felons; DD – Two cells state-side, occupied as stores; EE – Condemned cells; FF – Dark cells; G – Guard House; H – Hospital kitchen; I – Kitchen, state-side; K – Parlour, L – State kitchen; M – Lodge; N – Store; O – Guard House; P – Venereal Hospital; Q – Felon kitchen; R – Transport kitchen; S – Women’s lower kitchen; T – Small yard

The prison was three stories in height, one hundred and seventy feet long and one hundred and twenty seven feet deep. The front of the building, facing Green Street, was constructed of granite from the Dublin Mountains. It contained the hospital, a common hall, gaoler’s apartments, a chapel and guard rooms. It also had a pediment and platform with ‘apparatus for execution’[9]. One side was reported to contain only loop hole apertures which is where the poorest prisoners were located. They were compelled to suspend small bags from these apertures to beg alms to pay for their accommodations in a report from 1835[10].

The sides were constructed with a façade of black limestone and a round tower on each end. These towers were meant to contain lavatories which they did not in 1808 according to Warburton et al. At this time one was roofed in containing a room, one was the gaoler’s back yard and the other two ‘useless’. Cells for prisoners were twelve by eight feet, badly ventilated and the corridors onto which they opened three feet four inches wide. The authors were particularly critical of the interior space provided for separating ‘class of prisoner resulting in indiscriminate mingling’. The courtyard for male prisoners on the south was sixty one by fifty six feet with numbers per cell recorded as eight to thirteen.

The northern courtyard was separated into two sections; one fifty four by forty three feet for prisoners of a ‘better description; and one fifty four by seventeen feet for females with numbers per cell recorded as ten to fourteen. The overcrowding was particularly pronounced at ground level with empty cells on other levels. It is suggested this was so that guards and the keeper did not have to attend to them. The cells and hospital had limited bedding and linen and prisoners were invariably filthy. A lack of employment in the prison and crowding were seen as contributing to problems.

Warburton et al visited in 1812 and noted several improvements including:

- Cells on the upper floors now used with proper bedding and linens provided and infirmaries established.

- Three of the towers had been roofed and converted into six common halls and kitchens with fire places.

- The male felons yard walled off so that those to be transported were separated form others.

- Privies were regularly cleaned, fresh straw was provided once a month, an allowance of soap was provided to prisoners, daily sweeping and cleaning of the cells and whitewashing of the whole building three times a year.

- Three pounds of bread were provided to each prisoner three times a week if indigent, potatoes on Friday, herrings in winter and milk in summer.

Salaries in 1812 were recorded as:

Gaoler £400 (approximately £22,600 in December 2022); Deputy £113.15s; Five watchman £52 each; Local inspector £200; Chaplains: dissenting £100, established church £100, Roman Catholic £100; Physician £300; Surgeon £227.10s; City architect £56.17s.6d[11]

Even with these reported improvements, a reply to Henry Goulburn’s letter about the inadequacy of the prison by the Inspector General of Prisons in January 1826 agrees the prison is in a ‘crowded and melancholy state’. He affirms that Newgate provides sixty three cells and ten small rooms for an average of three hundred prisoners. The structure of the prison as a whole is deemed as totally inadequate for maintaining discipline, and unable to offer sufficient airing yards and day rooms or viable employment opportunities so the problems had not gone away. Conditions in the prison were not seen as a deterrent to crime or able to be a place of reform.[12] He goes on to blame the Grand Jury for refusing funds to build a new prison citing the ‘poverty of the city’. This would suggest no real improvement and the reports in 1835 would seem to confirm this.

The prison was finally closed in 1863, thirty one years after Thomas spent time there. It was demolished in 1893.

[1] Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent Saturday 28 September 1833 Accessed Britishnewspaperarchives 2020.

[2] The Pilot Friday 14 September 1832 Accessed Britishnewspaperarchives 2020

[3] Londonderry Sentinel 7 April 1832 Accessed Britishnewspaperarchives 18 January 2023

[4] https://howardleague.org/john-howard/ Accessed 19 January 2023

[5] History of the City of Dublin from the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time; containing its annals, antiquities, ecclesiastical history and charters; its present extent, public buildings, schools, institutions, &c. to which are added biographical notices of eminent men, and copious appendices of it population, revenue, commerce, and literature. Vol 2. Warburton, J., Rev Whitelaw, J and Rev Walsh, R. 1818. Published: London, T Cadell and W Davies. Accessed Internet Archives 18 January 2023.

[6] Topographical information. In Rob Goodbody, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 26, Dublin, Part III, 1756 to 1847. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, 2014 (www.ihta.ie, accessed 14 April 2016), text, pp 1– 106.

[7] ibid

[8] https://www.dib.ie/biography/cooley-thomas-a2008 Accessed 19 January 2023

[9] The Picture of Dublin or Stranger’s Guide to the Irish Metropolis Containing an Account of Every Object and Institution Worthy of Notice, Together with a Brief Description of the Surrounding Countryside and of its Geology. Published Dublin: William Curry Jun and Company New Edition 1835. Accessed 18 January 2023

[10] Ibid

[11] History of the City of Dublin from the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time; containing its annals, antiquities, ecclesiastical history and charters; its present extent, public buildings, schools, institutions, &c. to which are added biographical notices of eminent men, and copious appendices of it population, revenue, commerce, and literature. Vol 2. Warburton, J., Rev Whitelaw, J and Rev Walsh, R. 1818. Published: London, T Cadell and W Davies. Accessed Internet Archives 18 January 2023.

[12] Newgate Prison House of Commons 20 March 1826