“I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward” (David Livingston)

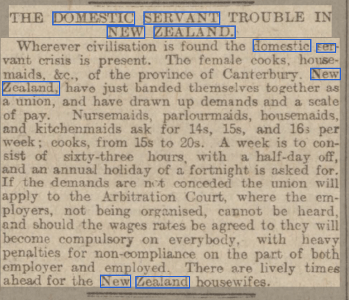

A Census of the British Empire in 1906 recorded Great Britain as ruling one fifth of the world. Domestic workers in New Zealand were calling for a 63-hour working week with a half day off and a fortnight off every year. Mount Vesuvius erupted devastating Naples and the San Francisco earthquake and fire killed close to 4000 residents.

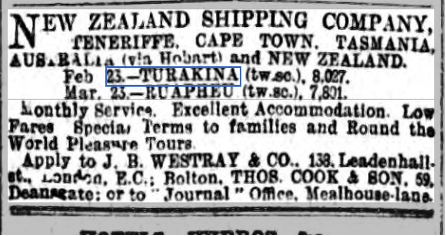

On 29 November 1905, my great grandmother Annie Webster left London for New Zealand on the steamship Turakina, a journey of some 24,000 km. The ship was fairly new, built in Dumbarton by William Denny and Brothers for the New Zealand Shipping Company. It had refrigerated cargo space to cater for the import/export market between Britain and its colonies. It could accommodate around 360 passengers, including accommodation for first- and second-class customers. The Turakina had completed its maiden voyage in late 1902 but had a short life – it was torpedoed and sunk less than fifteen years later on 13 August 1917 whilst carrying troops to New Zealand via New York with the loss of four lives.

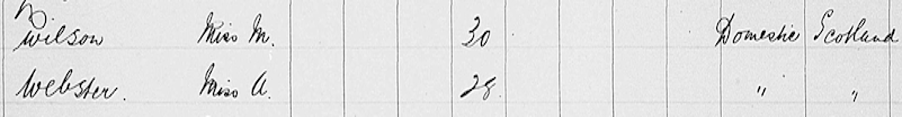

Annie was one of 168 third class passengers, and contracted to disembark in Wellington, New Zealand. She was on the same ticket as Miss M Wilson, both of whom are recorded as Scottish and domestics. It is not known all the reasons she chose to leave Scotland but a new start seems to be a likely reason. After 70 days at sea, Annie arrived in Wellington at 3.40 am on 16 January 1906 as one of 219 passengers and 5653 tons of cargo (Otago Daily Times, 17 Jan 1906) including livestock imported for individuals; pedigree sheep, fowls, bantams, pigeons and canaries (Marlborough Express 1906, Wanganui Herald, 1906).

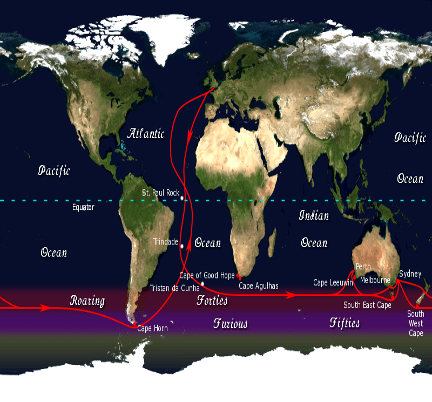

Although the Suez and Panama Canals had opened in 1869 and 1914 respectively, the New Zealand Shipping Company that Annie sailed with continued using the traditional route to Australia and New Zealand until at least later in 1914, with coal stops in Tenerife, Cape Town and Hobart.

The Turakina reported ‘moderate seas and winds to latitude 22 degrees south’, and ‘strong head winds and high seas’ to Cape Town which the ship reached on 22 December. She sailed again on the afternoon of 23 December, experiencing ‘moderate winds and seas’ in the Southern Ocean, before arriving in Hobart, Australia on 11 January. Twenty-three passengers disembarked in Hobart, along with the unloading of 361 tons of cargo and the ship left that same afternoon for Wellington (Lyttelton Times, 1906).

There was little time for sightseeing at designated stops. The Turakina arrived and departed from a fuel stop in Tenerife on 7 December. Such a stop was described by John Lynn in the diary he wrote in 1911 on his journey to Australia (Notes on Voyage, 1911: High jinks on the high seas. Edited by David Ransom 2021 and available on Amazon.com). Lynn noted that as they were due to arrive at Las Palmas, orders were given that money and valuables be put in the safe of the Chief Steward as locals would be coming on deck to sell their wares/fruit. He described the scenery of ‘gaily painted buildings of red, white, blue, and green at the foot of red sandstone hills’, fishermen, and boats full of locals coming to sell fruit, slippers, shawls, tobacco, wine, spirits, and chocolate. 300 tons of coal were loaded onto the ship in bags. On enquiring what wage per day [the coal loaders] received for ‘that dirty, hard work’ he was appalled to hear it was 1/- per day. In response he said he ‘is not surprised they do not want missionaries if the Englishman pays so little’, as it is a poor example of ‘Christian England’. It is likely that Annie experienced similar sights and sounds.

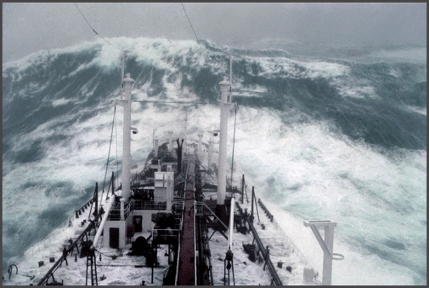

It is worth noting further experiences Lynn reported on as they are repeated in many a migrant’s diary of their journey over several decades. Recurring themes were the misery of seasickness on entering the Bay of Biscay. Rough seas resulting in general chaos were mentioned several times with personal items being thrown about in rooms; slipping from one end of the bed to another while trying to sleep; and dining in rough weather with meals ending up on the floor. On Lynn’s particular trip, he, at one point, reported ‘high seas with crests of up to 60 yards rounding the Cape…the vessel was below the level of the sea with waves breaking over them…noise like thunder, and rolling up and down and side to side’.

Unfamiliar sights described in some detail included flying fish, a battleship, porpoises, whales, the size of albatrosses, whales, phosphorus and the range of colours of the sea.

The passengers organised many of their own entertainments by forming a sport committee to plan races and competition, including an obstacle course, tug of war, wrestling and potato race. Games included cricket and football. On Lynn’s trip the carpenter made a bat, and the chief engineer a ball from wire and string. ‘Indoor’ activities included parlour games (chess, dominoes etc), quoits, reading and playing piano. The passengers also helped to clean the decks to keep themselves busy thereby helping to ‘curb weight gain from idleness’. One particular game, called ‘Catching the Train’ was explained in detail; it was open to all, including children. The course was to be completed four times with a coat over the arm:

- First circuit: find your boots jumbled in a bag with other competitors, put them on and lace them;

- Second circuit: eat a bun, as you missed breakfast, before you reach the starting point again,

- Third circuit: take a cigarette and light it on the run,

- Fourth circuit: take up a bag and complete the last circuit while smoking.

The range of temperatures would, for some, have been noteworthy on their own. The ‘oppressive heat’ near the equator resulted in several men and boys sleeping on deck and a “pillow fight’ with Lynn mentioning getting ‘quite the tan’ although some men were burnt with sore chests. He mentioned that ‘men were happy without boots and socks’: not that this was possible for the ladies. The water was warm enough to bathe in.

Once the Southern Ocean was reached Lynn found comfort from socks his mother had made with the dropping temperatures. Stories told to some of the women by the chief officer were of particular amusement. These included that in Australia rain was hot, hens laid hard boiled eggs because of the heat and Christmas puddings would cook if put on the front door step.

Why did Annie Migrate? Domestic Servants Needed

The Wanganui Herald, in September 1903 reported on the ‘domestic service problem’ in the colony. Wives and housekeepers nationwide had presented a petition urging Parliament to ‘inaugurate such legislation as will remedy the inconvenience…set forth and introduce by the assistance of Government a class of immigrants most urgently required,’ namely women who were both capable and willing to seek employment as domestic servants. The petition claimed ‘ever-in-creasing anxiety and trouble owing to the small number of young women willing to accept service as household servants.’ Causes of the problem where matters of congratulation owing to the conditions under which prosperity and opportunity was available in colony even as they created a burden. The causes highlighted included ‘the desire of young women to obtain situations outside of domestic service; the increasing demand for domestic servants caused by the rapid increase in the number of households; the continual absorption of unmarried girls into the state of matrimony; and the condition of prosperity which enables parents to maintain their children in home life.’

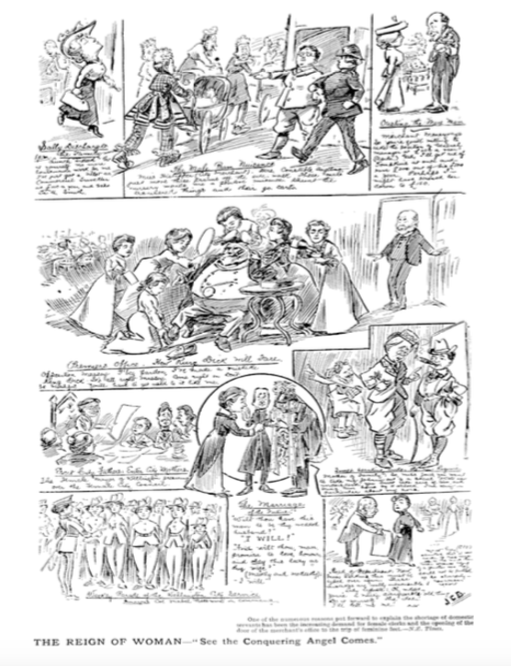

A cartoon of vignettes on the reversal of gender roles in the New Zealand Free Lance on 28 May 1904 identified ‘the reasons ‘for the dearth of female domestics in New Zealand’ under the moniker ‘The Reign of Woman – ‘See the Conquering Angel Comes’. Women’s suffrage had been a success in New Zealand and women where seen to be moving into more traditional male domains.

The cartoon claimed one of the numerous reasons to explain the shortage was “increasing demand for female clerks and the opening of the door of the merchant’s office to the trip of feminine feet”. The cartoon shows a selection of headings including ‘Sally Discharges the Family’; ‘The Male Pram Nuisance’; ‘Ousting the Mere Man’; ‘Premiers Office. How King Dick will Fare’; ‘Exit City Fathers: Enter City Mothers’; ‘The Marriage of the Future’; ‘Sweet hearting under the new Regime’; ‘Weekly Parade of the Wellington City Service’; and ‘Head of Department Now’.

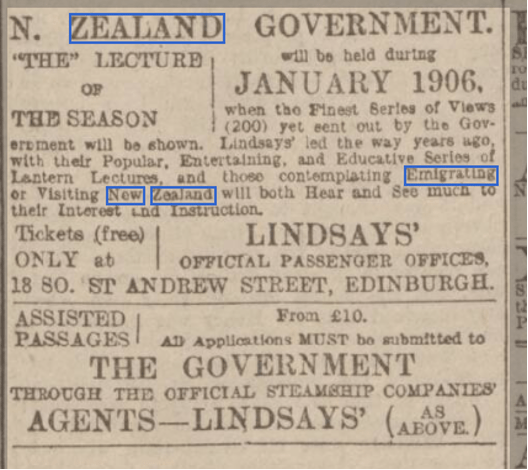

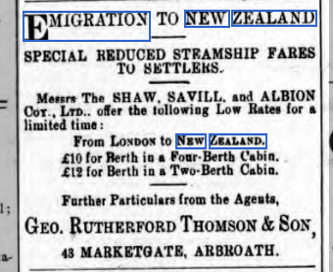

A new ‘reduced fare’ scheme for steerage passengers had been proposed by Colonial Treasurer and Minister for Immigration, Richard Seddon, in 1903 (the King Dick characterised in the cartoon above). It was anticipated that the New Zealand government and shipping companies would contribute to reduced fares and bonuses paid to passenger agents to encourage farmers, laborers and single female domestic servants from Britain to emigrate. The scheme was implemented and close to 37,000 immigrants availed of the fare between 1904-1915. Most single females described their occupation as domestics. It is possible that Annie attended a lecture on emigration sponsored by the New Zealand government, as seen in the newspaper image below. She was almost certainly aware of the advertisement in the Bolton Evening News and may well have been assisted by the British Women’ Emigration Association who ‘encouraged educated middle class women to emigrate’ to address population pressures in Britain and the ‘perceived problems of the number of superfluous’ unmarried women’(https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/45cb608a-08bd-3356-b14e-c620821b56dc)

The day before Annie arrived in New Zealand, another ship, the ‘Somerset,’ arrived in Auckland. A Herald newspaper reporter, said immigrants from the ship gave “a very doleful account of the labour market in the Old Country.” They highlighted the large numbers either unemployed or underemployed, with wages averaging not more than ten shillings a week over the previous two years. Relief work was failing to remedy the situation which was considered to be deteriorating. Labour conditions were of additional concern, with immigrants asserting that many would gladly emigrate if they were able to find the funding for themselves and their families.

An article in The Hastings Standard in 1905, eleven months before Annie set sail, explained the conditions under which new assistance to immigrate worked. It stated that:

“….the Ionic which arrived in Wellington last week brought nearly 400 third class passengers attracted here from the old world by the prospects in this new land. The policy of the Government is thus far proving successful as these immigrants have availed themselves of assistance in the shape of low fares offered by the shipping companies trading from Great Britain to New Zealand.”

The full rate for a steerage passage was £19, of which passengers had to pay £10. The New Zealand Government’s contribution was £4, and the shipping companies £5. Two passengers desiring a two-berth cabin, normally £21 for each individual, would be reduced to £12, with the Government giving £4, and the shipping companies the difference. Intending immigrants had to be approved by the colony’s Agent General and have at least £25 (approximately £2000 in 2017) over and above expenses to meet the cost of living in the interval between arrival and securing work. The article expressed concern that not enough was being done to procure domestics and mentioned the petition circulating regarding the matter, with proof of the dire need. An article in the Otago Daily Times in the same period expressed the opinion that the £25 condition should be modified as it deterred many and although some would need some provision to support them before they were employed “servant girls were…snapped up by eager employers and taken straight away from the wharf to situations.”

The Otago Times, late in 1906, was still highlighting the need for domestic servants, writing that ‘the Government has authorised the High Commissioner to grant assisted passages to domestic servants wishing to come out to the colony at the reduced rates provided under the scheme adopted some time ago. That means that each young woman would have to pay £10 to get to the colony’.

This was really interesting to read. The images really enhanced the story.

LikeLike

This is a very interesting read and I look forward to hearing more about how Annie gets on.

LikeLike

These stories are truly amazing; you have done so much research and really brought these people alive.

LikeLike

Thanks Sue!

LikeLike