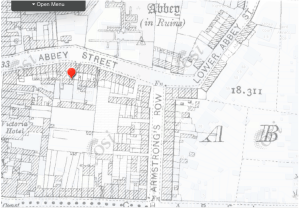

Historical newspapers can be a goldmine for developing a sense of neighbourhood, place and language. For my Anderson ancestors in Sligo on the west coast of Ireland this certainly proved to be so. Reports verified occupations, family relationships, locations and neighbours. This helped where other evidence were missing. William Anderson’s wife Margaret and children, found one way or another, are highlighted above. They were one form of 21st century social media in the 19th century.

The first mention of William and Margaret Anderson’s family in Sligo’s newspapers occurred on 12 January 1849 where William, master chimney sweep, and town officer John Jennings were praised for apprehending John Tiernan “in the process of stealing a carpet bag belonging to Mark Brennan from a car on the way to Collooney”[1].

From then most of the family were regularly recorded as they navigated relationships with, in particular, their neighbours. These episodes in their life provide an image of a rambunctious family as is shown in the following extracts as well as showing a little about types of cases and workings of the Petty Sessions.

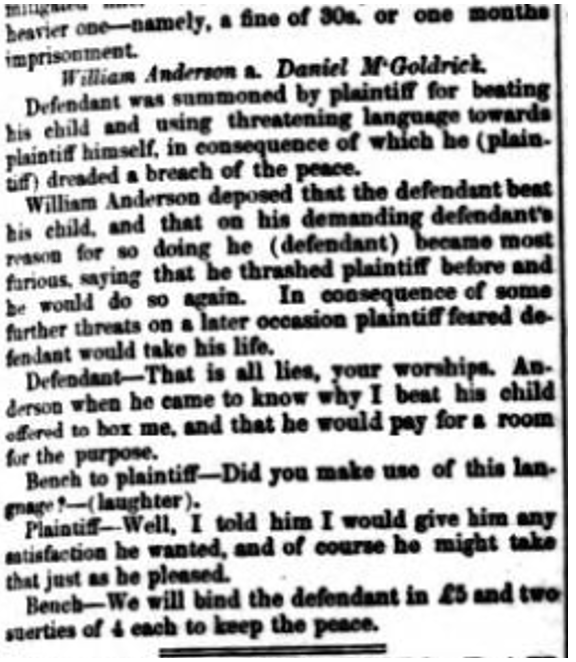

In 1856 William summoned Daniel McGoldrick “for beating his child and using threatening language towards himself, in consequence of which he “dreaded a breach of the peace.” McGoldrick claimed “he [had] thrashed [William] before and…would do so again”. Following threats William declared he feared for his life. McGoldrick denied this, stating “that is all lies, your worships. Anderson, when he came to know why I beat his child offered to box me, and that he would pay for a room for the purpose.” The bench asked William if he made “use of this language” to laughter from the court. William replied that “Well, I told him I would give him any satisfaction he wanted, and of course he might take that just as he pleased”. McGoldrick was bound over for five pounds and two sureties of ½ each to keep the peace[2].