Finding your way: Life in 19th Century Garioch

“Language is built on not only what is spoken but what is unspoken; the richness of the social structure…[and] other aspects form the words we speak and…how they are communicated” (Dame Evelyn Glennie (2019)[1]

In his book Thirty-Two Words for Field: Lost Words of the Irish Landscape Manchán Magan identifies 70 000 place names, over 4,300 words used to describe character and twenty one for holes. Living in Ireland and having Irish speaking friends has introduced me to the way that layers of knowing and understanding are made explicit through language.[2]

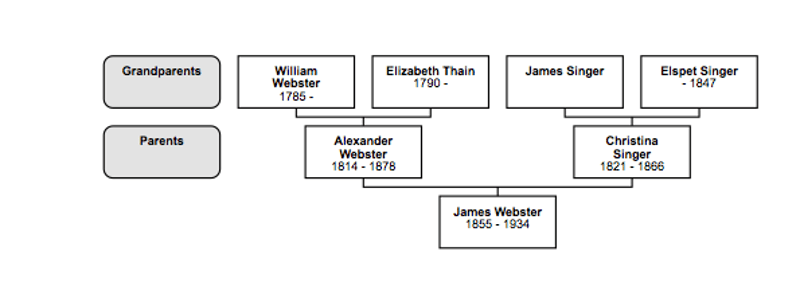

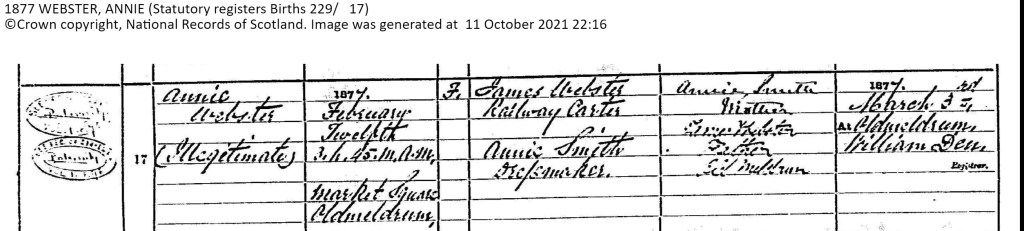

Helen Beaton’s (1847-1928) book ‘At The Back o’ Benachie (or Life in the Garioch in the Nineteenth Century)’, published in 1915, is a rich rendering of nineteenth century Garioch rural life and language. It is here, in the north east of Scotland that my 3x great grandparents Ann and her husband Robert lived, farmed and raised a family. (They are the grandparents of my great grandmother, Annie Webster of the last post). In this rural community social bonds were entwined through every aspect of local life. Shared language developed community cohesiveness and identity and rituals provided structure and a way to navigate life events by providing a ‘communally wise path’ and a way for emotion to be ‘contained and channelled’[3].

North East Scots or Doric has the most ‘maximally north-east features’ in the area of Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire up to the west of Inverurie.[4] Ann would have spoken and understood life and death through Doric. It is probable her experiences of courting, marriage, birth and death also mirror Beaton’s memories.

‘Scots’ is the native Germanic vernacular, descended from Northumbrian dialects brought in between the seventh and twelfth centuries of non-Gaelic Scotland. Broad Scots differs in sounds, structures and words; and also between fishing and farming communities within the same geographical area. Doric is known as such due to its association with the farming community.

Distinctive features of local Doric:

- Use of ‘fih’ in place of ‘wh’, for example, ‘fit’ for ‘what’

- Words local to the area, for example, cappie (ice-cream), stewie-bap (floury roll), and ficher (play with your fingers).

- Moon becomes mean, school becomes squeal, stone becomes steen[1].

Mrs Ann Smith wis baptised Ann Murison, it Bartholchapel on twinty July 1822. She wis the dother (daughter) o George Murison, a dominie (teacher) an his dame (wife) Barbara Scorgie. Ann merriet (married) Robert Smith on 27 May 1846 at the Chapel of Garioch and they hid fower bairnies (four children), three loons (boys) namyt William, Robert and Peter and a quine (girl) namyt Ann. They bed ootbye (lived out by) Bourtie it Old Meldrum. Robert deid in 1864 and wis beeriet (was buried) in Bourtie Kirkyard, along wit loons William who drooned (drowned) in 1871, aged 24 and Peter deid of peritonitis in 1874 aged 19.

Ann Murison exhibited significant resilience in her roles as wife, mother and grandmother. Care was ‘deep and rooted’[5] in rural areas and it is likely this, along with a strong sense of place in her community, helped Ann in her role as a stabilising influence for her family. From 1864 on until her death 36 years later in 1900 she faced the premature loss of children and husband, maintained then moved off the farm she had shared with her husband and cared for daughter Ann’s four illegitimate children. How much of these cultural influences, beliefs and practices did she pass to her daughter Ann and granddaughters Annie and Lizzie? And how much of them did my great-great grandmother Annie Webster keep close and incorporate into her own life?

Continue reading “Ann Smith (nee Murison): wife, mother, grandmother”