Historical newspapers can be a goldmine for developing a sense of neighbourhood, place and language. For my Anderson ancestors in Sligo on the west coast of Ireland this certainly proved to be so. Reports verified occupations, family relationships, locations and neighbours. This helped where other evidence were missing. William Anderson’s wife Margaret and children, found one way or another, are highlighted above. They were one form of 21st century social media in the 19th century.

The first mention of William and Margaret Anderson’s family in Sligo’s newspapers occurred on 12 January 1849 where William, master chimney sweep, and town officer John Jennings were praised for apprehending John Tiernan “in the process of stealing a carpet bag belonging to Mark Brennan from a car on the way to Collooney”[1].

From then most of the family were regularly recorded as they navigated relationships with, in particular, their neighbours. These episodes in their life provide an image of a rambunctious family as is shown in the following extracts as well as showing a little about types of cases and workings of the Petty Sessions.

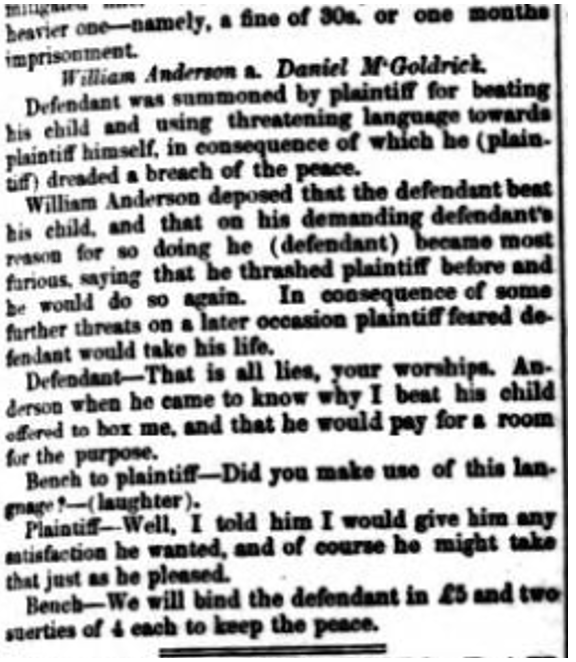

In 1856 William summoned Daniel McGoldrick “for beating his child and using threatening language towards himself, in consequence of which he “dreaded a breach of the peace.” McGoldrick claimed “he [had] thrashed [William] before and…would do so again”. Following threats William declared he feared for his life. McGoldrick denied this, stating “that is all lies, your worships. Anderson, when he came to know why I beat his child offered to box me, and that he would pay for a room for the purpose.” The bench asked William if he made “use of this language” to laughter from the court. William replied that “Well, I told him I would give him any satisfaction he wanted, and of course he might take that just as he pleased”. McGoldrick was bound over for five pounds and two sureties of ½ each to keep the peace[2].

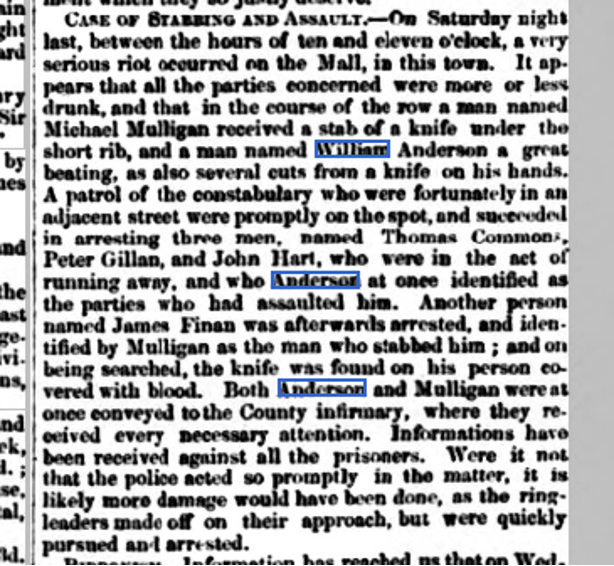

Just over a year later a stabbing and assault during a drunken riot on the Mall was reported. “In the course of the row a man named Michael Mulligan received a stab of a knife under the short rib, and a man named William Anderson a great beating…also several cuts from a knife on his hands”. Thomas Commons, Peter Gillan, and John Hart were arrested for assaulting William, and James Finan for stabbing Mulligan. “Both Anderson and Mulligan were at once conveyed to the County infirmary, where they received every necessary attention”[3].

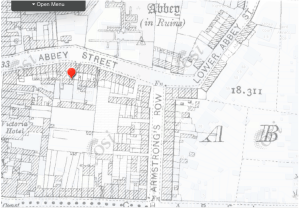

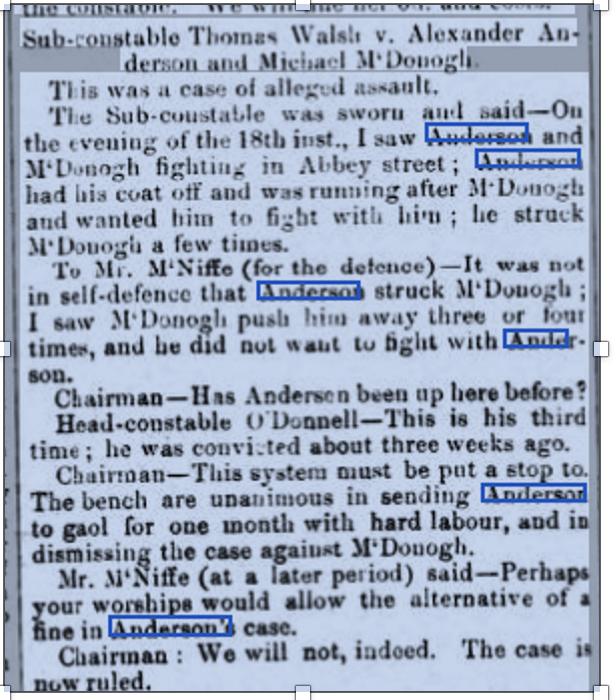

All seemed quiet until 1864 then hardly a year passed without some mention of the family. Firstly, William appeared at the Sligo Petty Sessions for quarrelling in Abbey-street. He was bound over in the sum of five pounds to keep the peace for twelve months. It appeared he interfered to prevent another man from being assaulted. On the same day, son Alexander appeared for fighting with a man named McDonagh on Abbey Street. As this was his third appearance, Alexander was sentenced to month of hard labour in gaol. The offence is recorded in the Sligo gaol records[4].

Two years later in 1866 publican John Brady deposed that William and his eldest son John had been in an altercation with Gregory Dunleavy; the trio rioting and breaking furniture on his premises at the corner of Wine and Quay Streets. Brady said that

“on the evening of the 12th of February, Dunleavy and Connolly with some others went to his house and called for drink: shortly after the Andersons went in to the kitchen, where Dunleavy was; the Andersons were not in the habit of going to the house; an argument of apparently an unfriendly nature began between the parties; after half-an-hour the Andersons went out and returned in an hour, and charged upstairs to where Dunleavy and his company had removed; he saw young Anderson strike Dunleavy, and old Anderson caught him by the breast; then a general row began; a shoemaker who went in with the Andersons was very violent…there was a regular riot and his furniture was broken…eight shillings damages caused to furniture…Andersons were sober. ”

The defendants were charged two shillings six pence each, ordered to pay a total of eight shillings compensation, and ten shillings costs, or be sent to prison for one week[5].

A year later William brought Peter Owens before the petty sessions with both parties arguing the other stole joints belonging to a chimney sweeping machine. William won the case. The newspaper reported that during the hearing William had “pulled the joints out of Owen’s hands in the presence of the magistrates, which was a contempt of court, and also an assault on Owens”. He was taken into custody, and a case of assault was entered on the books against him. For the contempt charge William’s lawyer said that “Anderson was a man of long family, and he believed it was not done through any disrespect of the court and…he hoped they would make it [fine] as light as possible in all events. The bench…decided on fining him two shillings six pence and six pence costs [instead of forty shillings]”[6].

In 1868 a number of the family where implicated in an incident involving a mob throwing stones at a shop owned by Patrick Gray on the banks of river. Patrick’s brother John was charged with assaulting William and Margaret’s daughter Mary Anne. The altercation was instigated when Thomas Brennan had to seek a refuge in a workshop from a mob. A man with Brennan, Nash, stated that “stones and clods were flying after Brennan; the two Grays ran out to keep back the mob…a Miss Anderson, struck one of the Gray’s on the head; and more of them went down to the slip and got an apron-full of stones which they fired into Gray’s shop”. The reason for Brennan seeking refuge is unclear.

Patrick Gray claimed a crowd assembled in front of his workshop around 4.30pm. Three female defendants (Mary Anne and Margaret Anderson and Bridget Mahan) were throwing stones into the workshop requiring him to duck down.

Mary Anne stated that on that evening

“she was sitting with her sister in a neighbouring house; heard a noise in the street, some people were running along; went over as far as defendant’s shop, defendant gave her a thump, knocked her down, and kicked her, and called her a common ______; she never gave him any provocation”. She said “I live near the Riverside and defendant lives near the hotel; I had not a stone in my fist; did not rush over to defendant to strike him with a stone; did not see any stones thrown into defendant’s house; there might be stone thrown into it, but I did not see them…Defendant kicked me when I was down…After I got up he tore my clothes”.

Witness, Alexander, of the 1864 three strikes sentence and Mary Anne’s brother was accused of not ‘kiss[ing] the book’. Magistrate, Mr Griffith, swore that “anyone who does not kiss the book wants to evade telling the truth. I would not swear him again”. After some debate between the magistrates, Alexander was again sworn. He deposed he saw a number going over Linenhall Street, heard his sister shouting out and found her “all besmeared with gutter, and her clothes torn…John Gray (defendant’s brother) had a hold of her; heard that defendant was after striking her.” In his statement Alexander claimed stones were not thrown until after his sister was assaulted, although he did not arrive until after the assault was over.

The next witness, Mary Anne’s sister, Margaret (my great-great grandmother) stated

“heard a noise down the street; [she and her sister] went down to where the noise came from; going down by defendant’s house defendant ran out and knocked down her sister; ran away when he saw her fall….There was a great number in the street; they were cheering; my sister did not throw a stone at that time”.

Later in her statement, rather reluctantly, she admitted Mary Anne did throw stones after being assaulted.

For the defence, Nash stated he did not see the assault but one of the Grays had an item in their hands. Patrick Gray claimed that seven of the Anderson family were involved. A lawyer replied “It was a great siege” to much hilarity. When asked if William threw stones, Gray replied that he hadn’t but threatened to “rip the belly out of me”. Twenty-eight stones were found in his workshop. Gray stated that the Andersons led the mob and he pushed away the girl who tried to fire a stone into the workshop. He stated he “never kicked a woman…I would scorn to do it” and admitted that ‘old Anderson’ did not mention the “abuse the daughter got.” Lawyer for the Andersons, Mr McNiffe asked “On your oath did he not challenge you to fight on account of the abuse you gave his daughter?” Gray replied “I would not condescend to leave my workshop to fight a sweep” and that he only pushed Mary Anne believing she had stones at the time.

Patrick’s brother John corroborated the testimony adding that Alexander used threatening language. Mary Anne’s mother Margaret said her daughter was beaten and Alexander went to her assistance, saying he would box the plaintiff. The case of Mary Anne Anderson versus Patrick Gray was dismissed and although magistrate Mr Griffith stated there was cause for threatening language and he would behave in the same manner if his daughter were struck, William and Alexander were each bound over for ten pound, and two sureties of three pound each, to keep the peace for twelve months and cautioned to conduct themselves properly.[7]

Two years later in August 1870 the family were back.[8] William and wife Margaret were brought before magistrates on charges of assault and threatening language. Neighbour James Hanney had served one of their sons with a summons for breaking the windows of vacant houses near Abbey Street. William had consequently taken umbrage and “came over to Hanney’s house roaring tremendously…accompanied by his wife and three daughters. They presented such a menacing attitude to the plaintiff that he concluded they were going to “flitter” him.

William called him an “old robber” and said that “for one farthing I would crush your bones to the earth”. Margaret is reported to have “stepped forward and left the impression of her fist over the plaintiff’s eye…[and] preparing for the second charge…she warn[ed] the plaintiff that she would take the life of the old robber.” William asked her “to stand to the rear, and allow him to go forward – that he would “do” the plaintiff himself, and “would tear him asunder like a lark” before inviting James Hanney to engage in a round of boxing which Hanney refused, saying “boxing ill became an old man of seventy years.”

William offered four half-crowns for the satisfaction of a short round and offered to have one hand tied while divesting himself of his coat and vest. Hanney refused, left and locked himself in his house. Four witnesses, including son John and daughter Mary Anne along with Edward Brennan confirmed events, although none saw Margaret physically strike Hanney although her hand was raised. The same complaint of threatening language was then brought against daughters Margaret, Bessy (who shouted “You robber, we will flitter you”) and Mary Anne.

Finally, an assault charge was brought against Bessy, Margaret and Richard Anderson by plaintiff Catherine McDonagh, the twelve year old granddaughter of Hanney. McDonagh claimed she was assaulted by the trio while outside with her little sister. She said while going up to the police barracks Bessy, Margaret, and Richard came up from her house and Bessy gave her a thump, got her hands round her, and knocked her down telling her brother Charles to strike Catherine with a stone. Margaret and Richard then hit her with Margaret telling Maryanne to go to the house for a hammer telling her to “be sure not to hit about the head, lest the marks would be seen, but about the back and chest”.

The Mayor had some choice words for the family, stating that:

“William Anderson and Margaret Anderson senior it is too bad that this town and this bench should be put to such trouble with you and your family. Your conduct is disgraceful. Scarcely a month passes that you are not brought up before this bench, for some offence or another. We have endeavoured, both by caution and fine, to put a stop to this state of things; and, at one time, we remitted a sentence of imprisonment to a fine, in the hope that you might conduct yourselves in future. I am sorry to see you and your family here continually. In this case, we require you, William Anderson, to give bail of twenty pound and two sureties of ten pound each to be of good behaviour for twelve months, or in default of finding such bail, to go to gaol for one month with hard labour. Margaret Anderson, we fine you ten shillings. You are the mother of a family, and were it not for that you would go to gaol.”

The case against the children Margaret, Bessy and Mary Anne was dismissed with the trio being cautioned about their behaviour. The Mayor stated

“it is very vexatious to have to deal with such a case, particularly when one family like this gives such an annoyance in the town. We are very reluctant to send these young people to gaol, which, perhaps, would make them worse, although some hold a different opinion, and believe that punishment in gaol will correct bad conduct which parents often unhappily overlook. It is a shame that parents would inflict such disgrace on themselves and on the town by such conduct as this”.

The children were each fined ten shillings with a third to go to the plaintiff.

Six months later, son John was implicated in the death of a man from Ballyshannon found drowned in the Garavogue River named Francis Rogan. It was rumoured he had been beaten at the Riverside and thrown in the river. Rogan was last seen after an altercation in Armstrong’s Row near where John lived. That John was involved in an altercation with the intoxicated man is not in dispute.[9]

James Hanney from Abbey Street gave a statement saying

“I heard a quarrel in Armstrong’s Row…I went out and saw John Kearins [Sergeant] standing at his own door; I then went to the corner…heard Kearins say, “bring in that man;”…his servant then went up and brought in Anderson from the place where the deceased was lying dead; no one was then on the street except Kearin’s housekeeper, John Anderson, and the man who was lying stretched on the ground; the man lay on the street motionless, without a word, outside the window of William Anderson’s house; I did not see John Anderson do anything to the man…the man lay on the street for about ten minutes; he drew a sigh, and rose; he faced up towards the chapel; I thought he was going to the barrack; he said, “Oh, you mouse-coloured rascal, you’ve murdered me; come out now and do me…in a few minutes afterwards I heard the man opposite my door; he lay up against Gilgan’s house, and again he repeated the same words…the man moved towards the river along the wall; and when he was half way down the road, he staggered off the kerbstone onto the street…I have not been on terms with the Anderson’s for a year past; I fell out with them because they broke my windows; that was the cause; the man who cried out on that night had a North country accent”.

Kearn’s housekeeper Bridget Heally stated she and Kearns saw John come towards a man who appeared to strike him before they grappled, both falling to the footpath. The verdict of the coroner was accidental death by drowning although assault before death was evident in his injuries. It seems he wandered down to the river and fell in.

A few months later a report was prefaced with the phrase ‘The Andersons Again!’ with William ordered to pay twenty pound and another two sureties of twenty pound each to be on good behaviour for twelve months or go to gaol for two months. He was kept in custody until the bail was produced. These are significant sums, close to £6000 in 2023. The judge said that the “Anderson’s conduct had been disgraceful, and he and his family had been a common nuisance for a long time in the town.” William and Margaret were charged by Anne Tighe with abusive language meant to cause an estrangement between her husband and herself and she threw herself on the protection of the court. She claimed it was “a very indelicate nature and went to show that the Andersons made use of language towards her relative to her children, the most offensive and disgusting that could be used towards a mother”. Son John was called to give evidence in favour of his father, but his testimony was reported as “so revolting that the bench peremptorily ordered him to leave the witness chair”.Tighe was given the courts protection and the court said that “gross conduct was even aggravated by Anderson producing his son who had disgraced himself by the statements he had made”.[10]

In 1872 William brought a case against neighbour Jane Kelly for abusive language towards six year old son Charles. The case was dismissed and Mrs Kelly warned against a repeat for if proved she would be severely punished. Margaret Anderson then brought a case against Mrs Kelly claiming assault

where “the parties met in the street, and being in a warlike mood Mrs Kelly struck the complainant with a basket of fruit, alleging as a reason for the proceeding that her liberty of progression was impeded”. Jane Kelly was fined two shilling six pence and costs.

The court said that “there appears to be a very bad feeling altogether between these people. It is a pity they can’t live like neighbours.” [11]

In 1875 it was young son William’s turn. He was caught up in a case against a publican in Quay Street. Sixteen year old William was on the premises illegally with friends James and Michael Cochrane. The constable said “They are three characters, and I don’t know where you would find their equal.” William said he was a sweep, worked with his father and his brother was in the reformatory. I suspect this was Alexander. The chairman told him he was going in that direction himself. The Cochranes and Anderson were fined four pence each or one month’s imprisonment.[12] In 1877 William junior was charged with being drunk and disorderly at the athletic sports. William said “he was after coming out of the infirmary and he took a little drop which prayed on him.” He was fined five shillings and costs and then charged with assaulting John Sheridan who was standing with two friends at the hay corner. Apparently William and a friend named Ox had some words about ‘ould stobs’, and William struck Sheridan on the back of the head with a stick for which he was fined ten shillings and costs. William senior took him home.[13] In 1879 he was charged for desertion or absence from training with the Sligo Artillery and fined two pound or to be imprisoned in Sligo Gaol for two calendar months. He paid.

In 1877 William and Margaret’s thirteen year old son Richard and his friend James Foley where both fined five shillings and costs each for playing the game “pitch and toss” on a public road.[14]

It wasn’t until 1879 when another flurry of incidents were reported with one of the William’s “violently assault[ing]” Richard Kilmartin. He was fined five shillings or to be imprisoned on the ship Garl for one week. He paid.

The next case for William Senior was an alleged assault in Armstrong’s Row against Michael Gilmartin in 1879. Gilmartin turned up to court drunk as was pointed out by William’s lawyer. The reporter wrote that

“[his] face from the effects of his injuries presented an appearance scarcely less than hideous, turned very indignantly upon Mr Molony for making the accusation referred to, but only with the effect of clearly demonstrating the truth of it. He was at once amid considerable merriment ordered out of the box.”

The case was adjourned.[15]

Another newspaper recorded the same case as follows

“Gilmartin, whose prominent proboscis was decorated with sundry layers of diachylon plaster, came into the witness box in such a way as to convince all in court that he was slightly “under the influence.”[16]

The following week the case was heard in which William and his son Richard were charged with assault. It appears that Gilmartin had gone to William’s house while drunk to demand wages. He admitted he was insolent when William refused to pay him and said William pushed him out the door and kicked him. Consequently he cut his face while falling. His daughter Mary Ann Gilmartin swore

“she saw old Anderson push her father out, and Dickey Anderson followed him out, came behind him, and struck him a violent blow, which knocked him down. When taken up, her father was covered with blood. William Anderson was not there when his son struck my father. I do not know where Dickey Anderson is now”.

Witness, Edward Clancy, employed by William stated that

“Gilmartin entered his master’s house on this day under the influence of drink. He asked was he welcome. Anderson told him he was if he behaved himself, telling him it would be decenter for him to be at home with his wife. Gilmartin demanded a day’s wages, and Anderson said it was only a “three quarters” he owed him. Then Gilmartin asked to get this, but Anderson told him he was afraid he would drink it, and that he would give it to his wife. Then Gilmartin got insolent, and Anderson pushed him out. I swear I did not see him kick him”.

Son John who lived opposite agreed with the evidence so far, adding that William gave Gilmartin a kick then went toward Castle Street. Gilmartin returned and again tried to force his way into the house and was put out receiving his injuries. When asked if he knew who injured Gilmartin he said he did “but am I obliged to tell it”. When told he was he admitted it was Richard but “did not know where his brother was, no more that the whereabouts of the man in the moon”. William was fined 5 shillings and costs.

Williams contract with the Sligo Board of Guardians for the workhouse was recorded for over twenty years for which he earned £10 for sweeping all chimneys and flues. The last was confirmed in the month before his death. [17] Unfortunately the contract was rescinded soon after his death with the board showing little faith in young William Junior to continue in his father’s shoes. Most of the family who I have managed to trace to date are found in England soon afterwards. If anybody is related and wishes for full transcripts of the appearances I am happy to email them.

[1] The Sligo Journal Friday, January 12, 1849

[2] Sligo Independent on Saturday 12 January, 1856

[3] Sligo Independent, Saturday 11 April, 1857

[4] The Sligo Champion Saturday July 2 1864

[5] The Sligo Champion 24 February 1866

[6] The Sligo Champion 13 April 1867

[7] The Sligo Champion, Saturday 21 November, 1868

[8] The Sligo Champion, Saturday August 6 1870

[9] The Sligo Chronicle, Saturday, February 25, 1871

[10] Sligo Champion, Saturday August 5, 1871

[11] Sligo Champion – Saturday 21 December, 1872

[12] Sligo Chronicle, Saturday 19 June 1875

[13] The Sligo Champion, Saturday August 18, 1877

[14] Sligo Champion – Saturday 6 October 1877

[15] Sligo Champion – Saturday 3 May, 1879

[16] Sligo Independent – Saturday 3 May, 1879

[17] Sligo Champion 19 March 1859, 22 March 1862 and 17 March 1877