It takes ten minutes to walk from my home to the Broadstone Luas stop near Grangegorman in North Dublin. Broadstone is opposite Kings Inn Park, Irelands oldest school of law and the home of the ‘Hungry Tree’ on Constitution Hill, a short walk to a previous tenement turned tourist attraction at 14 Henrietta Street, and 750 metres to St Michans Park, the site of the former Newgate Prison in Dublin on the corner of Halston and Little Britain Streets. It is an area full of historical importance that is not so immediately obvious today. But what do these areas have in common, why this photo, and how are they connected to Thomas?

Image of Bully’s Acre Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland Personal Photo Denise Brown

The photo is of a place. Thomas Finlan left no photo of himself, it was too early for that. The place, Bully’s Acre, was a burial ground he perhaps knew rather well. It is connected to events and conditions, unimaginable for many of us, that he lived through and which I imagine influenced his decisions. Additionally, his stomping ground then is partly mine today which is somewhat strange to me. I am not from Ireland and never imagined that one day I would live here.

One of the newspaper reports of Thomas’ arrest for highway robbery in 1833 stated that

“In about 2 hours, after Dunn was taken into custody, Peace officers McDonagh and Scott arrested a well-known resurrectionist, Thomas Finlan, as he was coming out of a public house on Mercer Street…Finlan was immediately identified as the person who had attacked Mr Dunroche…it is only due to the police these arrests have been made…one of the most daring gangs that ever infested the neighbourhood of this city has been at length arrested…

Another clue to his life is in the Dublin Weekly Register Saturday 28 September 1833 that states:

In the neighbourhood of Charlemont and Leeson streets for several nights roads have been infested by a gang of robbers…a watch stolen and traced to a pawn shop where a woman was arrested and stated she had got the watch from a resurrectionist, John Hart living in Bow-Lane. [6 people were arrested and Walsh and Hart were identified by name]. Police are confident the entire gang will be brought to justice.

As you can imagine, finding out Thomas was a resurrectionist in addition to highway robber was a bit of an eye-opener. Another article mentions his incarceration at Newgate which is mentioned in the introduction to this post, and Hart and Walsh were both mentioned in articles as co-conspirators with Thomas. In addition, Bow Lane where Hart lived is in close proximity to Bully’s acre which was one hot bed for those wanting bodies to sell to medical students and doctors. I will write more about resurrectionism and Thomas’ other crimes in another post but in this one I want to focus to the cholera epidemic of 1832 which he lived through and survived.

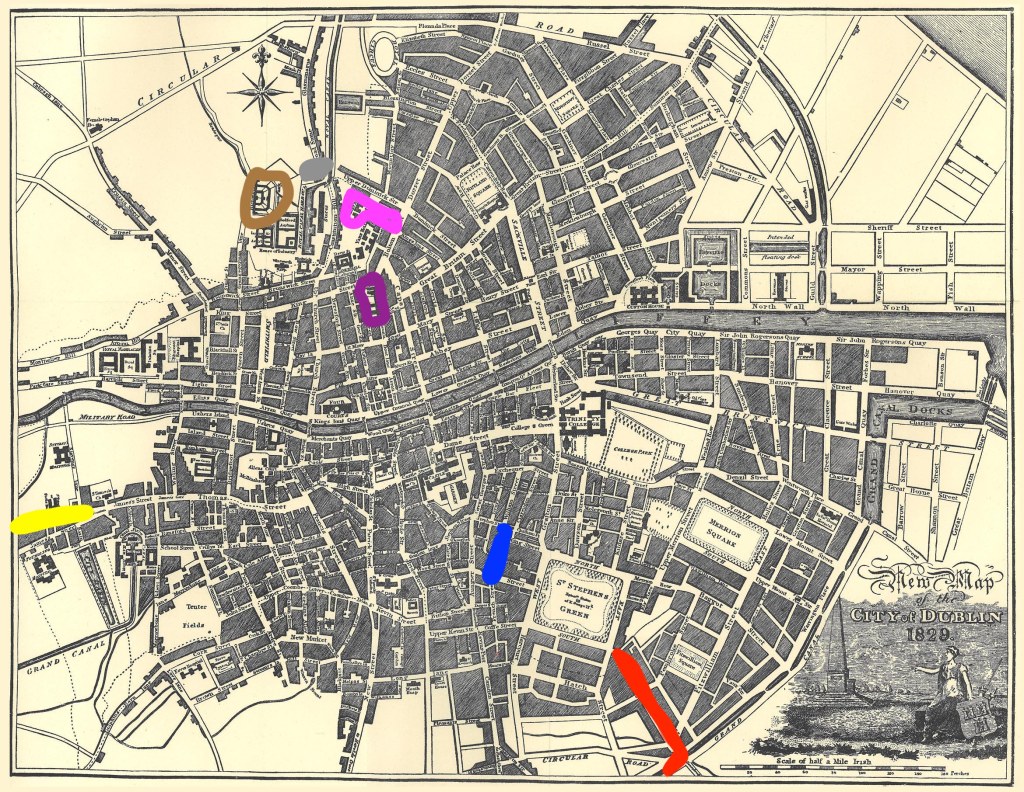

Dublin City 1829

Key: Brown: Richmond Fever Hospital, Grey: Broadstone Luas Stop now, Pink: King’s Inn and Henrietta Street, Purple: Newgate Prison, Yellow: Bow Lane, Blue: Mercer Street where Thomas was arrested, Red: Leeson Street to Charlemont

The outbreak of Asiatic Cholera in March 1832 in Ireland which had already killed millions across China, India, Russia, Europe and England was not unexpected. Whole families could be wiped out by a micro-organism that thrived where sanitation was poor and slum housing was common. The majority of Dublin’s residents invariably had no access to clean water and sanitary facilities. A lack of understanding of the cause contributed to the death count with victims suffering from uncontrollable diarrhoea, severe stomach cramps and vomiting. Reasons for the disease were blamed on miasma theory (a ‘killer fog’) to punishment from God for wickedness.

When preparing to expand the Luas (tram) lines to connect the North and South sides of Dublin City archaeologists discovered a mass grave at Broadstone in Grangegorman. It contained victims from the outbreak. In the early days many victims were buried at Bully’s Acre (Hospital Fields officially) by Kilmainham Gaol. For example, around five hundred souls are reported to have been buried in only in ten days from late April to early May in 1832. As you can imagine the ground was soon severely oversubscribed. It was closed to cholera victims and those not belonging to the Parish of St James in May and then temporarily closed completely at the end of June 1832[1]. Victims where subsequently interred in a trench at the aforesaid Grangegorman which was especially opened to cope with the numbers of dead. The trench is where a footpath now joins the Luas stop with the Grangegorman Dublin Institute of Technology, of which the still standing clocktower building was once Richmond Penitentiary and the location of the Dublin Cholera Hospital. The doors of the hospital once daily bore the names of the deceased. Deaths in Dublin in July 1832 were reported to be in the vicinity of three hundred to three hundred and fifty weekly.[2]

Bram Stoker’s mother’s personal reflections of the outbreak in Sligo which saw a death rate of around forty seven percent of afflicted victims is said to have influenced his well-known novel ‘Dracula’.

Bram Stoker’s name is familiar to most due to the success of Dracula, although it is not always known that he was Irish. Stoker was born to Charlotte Thornley who was only fourteen and living in the centre of the Sligo when the cholera epidemic hit. She lived only 200 metres or so from Sligo Abbey whose burial ground was another over-subscribed during the epidemic. It is said that her stories influenced Stoker’s writing: Dracula’s first victim was ascribed the same date as the first death from cholera in Sligo – namely 11 August.

Charlotte’s ‘Experience of the Cholera in Ireland 1832’ was written in Caen in France in 1872. She records that “our world was shaken with the dread of the new and terrible plague which was desolating all lands as it passed through them” (p.11).

Her remembrances are harrowing as she describes the dread as whispers of the disease coming closer spread across Ireland, and the failing of human sensibilities and humanity as fear overtook men. Charlotte described how trenches were cut in roads to prevent people crossing, the clergy fled from infected areas, bar one, a Roman Catholic priest who told her family ‘he sat at the top of the stone steps in the Fever Hospital with a horsewhip to prevent patients not yet dead being dragged down the stairs by the feet and buried ‘not yet dead’ to make room for new occupants’. She described Sligo as becoming the ‘city of the dead’ within a few days, with no rhyme or reason for a house that was spared or one that would lose many of its inhabitants. Fortunately for Charlotte’s family they owned a cow and chickens and were reasonably self-sufficient. They were able to supply milk to neighbours in need as well. Their street also had a new sewer running through it – one of only a few.

She remembers seeing neighbours being carried away and perhaps most poignantly begging her mother to allow her to go next door to comfort a little girl who was alone crying. Her mother agreed and the child died an hour later in her arms. She returned home to be fumigated. Remedies against the disease she remembers include plates of salt placed outside doors and windows on which acid was poured and daily doses of whiskey and ginger. They apparently had a store of cholera medicines although Charlotte does not tell us what they were. Tar barrels were burnt in the streets to purify the air and carts tolled with attached bells. A coffin maker would knock on doors inquiring if a coffin was required – the family poured water over his head when he refused to desist. Only two homes in the street, including Charlottes, did not lose a family member. The family eventually fled the town, after some of their chickens were found dead, only to face mobs who were fearful they carried the disease with them. On reaching Donegal they feared for their lives in the face of mob agitation at their appearance. They eventually were able to stay with family in Ballyshannon although the whole house was quarantined by the authorities for several days. When they eventually returned to Sligo they found 5/8ths of the population deceased or gone and grass grown streets.[3]

Historian Dr Fiona Gallagher believes it is likely the location of Charlottes home saved the family – they were elevated above the river and probably had their own well.[4] She writes that conditions in Ireland contributed to a conservatively high death toll of around fifty thousand nationally. It arrived via Belfast in March 1832 and subsided finally in the spring of 1833. The population was mostly poor and with periods of regular stints of typhus, famine and wet summers resulting in shortages of food and fuel in several decades before the outbreak the country was primed for the easy spread of fever.[5] The epidemic was expected and was already feared before it arrived. The Irish Central Board of Health was re-activated in 1831 to oversee local boards, distribute grants and act as a watchdog to combat the arrival of epidemics. Local boards were set up and authorised to manage ‘conditions’ i.e. set up hospitals to cope, whitewash houses, clean up lanes where the poor lived by removing manure heaps and washing the area, burn unclean bedding and manage the outbreak of disease. The public were urged to seek medical attention or run the risk of death if afflicted. Cases were sent to temporary cholera hospitals, weekly reports were published in newspapers and sufferers ordered to isolate for fourteen days after recovery. Cleanliness, fumigation and special transportation carriages for the sick were encouraged along with warnings about public gatherings and the cessation of wakes and funerals. Other preparations for the arrival where varied according to place and included bans of sale of second hand clothing and proposals to erect mobile privies. Quarantine measures at ports and on travel between towns was controversial partly for commercial reasons. Central Board of Health grants equal about £14 million in sterling in 2021[6].

It can’t be known what Thomas’ fears, choices or experiences living through this epidemic where. He is recorded in later documents as able to read and write and his occupation was groomsman and coachman. How did he fall into a life of crime? Was he employed at the time or one of the many urban poor? They are questions which are impossible to answer.

[1] http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/epubs/bully%27sacre.pdf ‘Bullys Acre and Royal Hospital Kilmainham graveyards: history and monumental inscriptions editor Sean Murphy 1989 Oivelina Publications Dublin

[2] Ballyshannon Herald Friday 20 July 1832 Britishnewspaperarchives accessed 2022.

[3] Charlotte Stoker, Experience of Cholera in Ireland 1832 in The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature No 9 (Bealtaine 2017) pp. 11-18. Swan River Press at https://www.jstor.org/stable/48536136

[4] Life under lockdown: the 1832 cholera epidemic as seen by Charlotte Stoker May 2020 by Marion McGarry at https://www.irishhumanities.com/blog/life-under-lockdown-the-1832-cholera-epidemic/

[5] ‘Mapping the Miasma’- Ireland’s 19th century Pandemic: an analysis of the 1832 Cholera epidemic by Fióna Gallagher at https://www.irishhumanities.com/blog/nemapping-the-miasma-irelands-19th-century-pandemic-an-analysis-of-the-1832-cholera-epidemic-w-blog-article/ accessed 14 January 2022

[6] Cholera: Fever, Fear and Facts: A Pandemic in Irish Urban History https://www.drfionagallagher.com