The texture of life on board an emigrant ship in the nineteenth century required a modicum of patience to cope with a dire lack of personal space, and was run on a regimented system within a framework of rules set according to the values of Victorian Britain. Emigrants came with distinct languages, customs, beliefs, prejudices and institutions. As on land, they were divided along social lines in every aspect of shipboard life. Emigrants were strictly separated according to class, marital status and gender. There were rules and expectations of behaviour on matters of morality that continued to cause consternation to authorities throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. Improper liberties, especially among single men and women, blasphemy, language, gambling, and violence were strictly monitored. To further complicate matters, divisions along lines of religion and ethnicity played out as discomfort and tensions increased.

Emigration was a defining event for Sutherland, McIver and Webster individuals and families, so what set of circumstances encouraged them to emigrate on a lengthy, uncomfortable and risky voyage? For John and Mary Sutherland, County Sutherland, their home in the far north of Scotland was infamous for both the organisation and scale of the clearance of tenants from the interior of the estate to its coastal regions for sheep. Between six and ten thousand people were removed from their homes between 1807-1821 alone. It has been described as an ‘extraordinary episode.’[1] The next three decades saw the collapse of the kelp industry, potato crop failures in the 1830s and 1840s, a severe winter in 1837 and typhoid and scarlet fever.

Regulation of Labourers Wishing to Emigrate to New Zealand (5 Dec, 1839)

The Company is to set aside seventy five percent of purchasers money to assist in the costs of emigration. Land purchasers are encouraged to submit names of labourers for free passage, inclusive of provisions and medical attendance. Preference given to those engaged to work for the capitalist.

Occupational expertise required: agricultural labours, shepherds, miners, blacksmiths, farriers, sawyers, tanners, brick makers, carpenters and cabinet makers, tinmen, bakers, tailors and boat builders (a selection).

Requirements for immigrants (not land purchasers):

- Immigrating to work for wages, under thirty years and married (marriage certificates must be produced).

- Testimonials provided attesting to qualification, character and health.

- Wives have free passage with husbands; single women accepted if under certain protections: travelling with either parents, close relatives or servants of ladies who are cabin passengers.

- Vaccinated against smallpox or have suffered from the virus.

- Costs of reaching port of embarkation to be borne by the emigrants.

- Emigrants must procure their own trade tools and provide themselves with the clothing, bedding and necessaries as laid out by the company.

- On arrival immigrants suppled their immediate needs, assisted in reaching destination, and employment if necessary although able to work for whomever they chose and negotiate a wage.

The New Zealand Company’s selling point for attracting emigrants was ‘opportunity to prosper and move up the social ladder.[2]’ Land prices were promised to be in the reach of any hard working individual or family. It was summed up rather succinctly by colonist Dr Evans, ‘the emigrants…principally of the labouring class…would, by going out to the new colony, escape from the ruinous effects of that competition from which that class [are] suffering so severely in this country’[3]. Dudley Sinclair, whose family were from Caithness but lived in Edinburgh, was through his mother, a nephew of the Tollemache brothers who had been involved with the New Zealand Company from its inception. Sinclair bought nine balloted land lots before emigrating on the Oriental in 1839 with friend Richard Barton, previous Superintendent of Estates to the Duke of Sutherland. Purchasers of land were encouraged to put forward the names of labourers for emigration for company approval, which evidently Sinclair and Barton did. Barton took with him a party sponsored from the Sutherland estate, including newly-weds John Sutherland and Mary Gordon. The Duke of Sutherland was keen to reduce the population of the region and provided his support. Promises of employment if not already contracted were given so it probably seemed a very good deal for many whose prospects seemed grim.

On 15 September 1839, at the end of what proved to be an unusually wet summer, the ship Oriental, moored below the town of Gravesend, was towed down the Thames as the cheers of onshore well-wishers wished it well on its journey south to New Zealand. An article published 16September 1839 described the toasting and farewells of those about to leave and reported the weather as very unfavourable. The journey took 138 days (over five months) before arriving at Port Nicholson in New Zealand and Mary gave birth to her first child Elizabeth on 14 June, 1840, just over four months after arriving. She would have conceived early October, and spent the early months of her pregnancy aboard a ship that, undoubtedly, like most others in the period, suffered from problems the rats, cockroaches, fleas and bed bugs that infested living areas, the stench of drains and bathrooms that were often blocked, the tedium, lack of ventilation, overcrowding, noise, and the difficulty of completing everyday tasks such as cleaning, washing and cooking.

Oriental Details

| Vessel Details | Other details (NZ Register copy) | Cabin passengers | Steerage passengers |

| Barque of 506 tons sailed from Gravesend 15 September 1839 arriving in Port Nicholson 31 January 1840 after 138 days. All passengers were finally discharged 15 February. | 66 married couples 29 single men 3 single women 17 children (aged 9 – 14) 9 children (aged 1 – 9) 8 births and 3 deaths | 20 persons | 134 persons |

The months emigrants spent on board would prove to be different from both the ‘lives lived before’ and the ‘lives yet to come’. It is imagined that the bonds formed by the Sutherland’s both before and during sailing were useful for their first few years in the colony. Although life on board replicated features of the accepted social structure of the nineteenth century, distinctions often blurred both during the trip and on arrival. This was certainly the case according to early diary entries of those who observed the first few months onshore. On losing sight of British shores it was undoubtably common knowledge, although possibly not true understanding, that there was “no going back” and emigrants would find themselves ‘liv[ing] in an exotic maritime limbo full of unfamiliar sights, sounds and customs with its own special oceanic perils such as storms, icebergs and the perennial fear of fire.”[4] You can break the journey into six distinct phases based on common comforts, discomfits and personal events, starting with the leaving, which is what I will attempt here.

Phase 1: The Leaving

There is little evidence of the Scottish contingent leaving their home in the far North of Scotland except for that recorded in a poignant poem written by the New Zealand descendant of Alexander Sutherland and Elizabeth MacKay who were aboard the same ship. Author, Fiona Kidman writes “at that moment as the keening arises, the wife of Alexander Sutherland holding her youngest child in her arms breaks down and refuses to board to go one step further”.[5] She further details the event at Brora in County Sutherland of Alexander taking their daughter and turning back to the boat which would ferry them south. Alexander’s determination and taking charge of their child was surely incentive to leave all she knew and cherished behind. It is unknown if the families of John and Alexander were related, although Alexander was an executor to John’s will on the occasion of his death and John and Mary often stayed with Alexander and his wife Elizabeth when visiting Lyall Bay in Wellington. We also know from the Surgeon Superintendents Journal that he took charge of emigrants on 10 September 1839 as the ship lay in the Basin outside the West India Docks in London[6] so this is likely where the Sutherlands boarded the Oriental. They would have then been towed by tug to Gravesend, a journey of a day.

Docks and Basin in London[7]

Bustle and confusion were the order of the day at ports. It was usually several days before ships had completed the outfitting required for the journey. Carpenters would fit out the hold with tiers of bunks, and loading cargo would be key activities. Steerage, where the Sutherlands were housed for the journey, was usually separated into four vertical divisions with crew housed under the forecastle, a compartment for single men, and a compartment in the stern for single women (who were repressively monitored) separated from the men’s by a central compartment for married couples and children. Temporary wooden bunks and head-high partitions with curtains at the foot would be constructed and then removed for the return journey when vessels would be filled with cargo. Emigration depots were eventually built to house and acclimatise intending emigrants waiting to board. Before this, hostels and the wharf itself where common accommodations.

A common feature appears to be the sight of what brings to mind an open market on deck with a plethora of passengers, cargo and livestock milling around. That this attracts merchants is not unexpected, with sales of last minute supplies a roaring trade. A passenger on the Tweed in 1874 reports Irish Whiskey being sold at a great rate.Missionaries also used this time as an opportunity to distribute a range of religious documents and emigrants were examined by a doctor appointed by the Board of Trade in an attempt to prevent infectious disease from becoming problematic on the journey.

Emigrant life officially started with a state of general confusion. The annoyance of one emigrant is evident as he describes “children…squalling…women grumbling and scolding…men banging about”[8] This perhaps reflects the span of emigrant emotions, variously described as a mix of sore hearts, tears, jitters, excitement and a visible wrench. There are “a cloud of witnesses to tell us what it was like to be there” for all phases of the journey.[9]Regrettably, John and Mary’s voices are lost but we glean common feelings, concerns and fears when exploring these aspects of the migrant experience. The Sutherlands would have already made their farewells in Brora; although perhaps not their peace with leaving. Emigration was destabilising and links with close family, friends, and community were often, although not always, irretrievably severed.

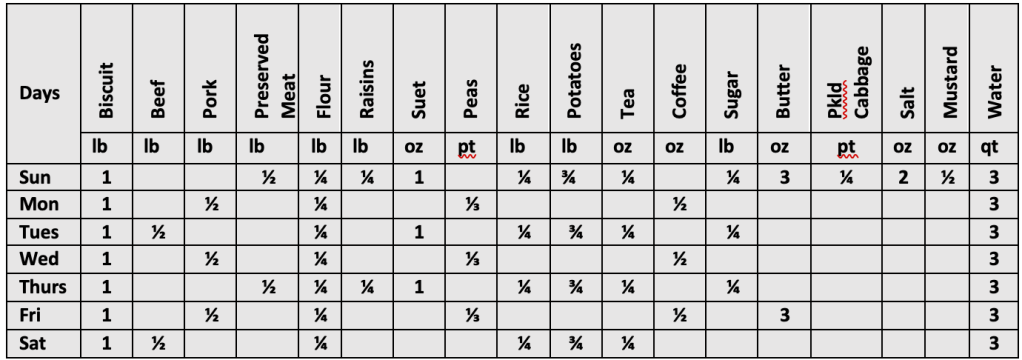

Rations for emigrants on New Zealand Company Ships in 1839 – Information relative to New Zealand compiled for the use of colonists by John Ward, Esq. Secretary to the New Zealand Company. 2ndedition. London: Harrison and Co., Printers, St. Martin’s Lane. Published Dec 1839 (Appendix No. IX. Dietary of Steerage Passengers; the Passengers to be in messes of Six or more, according to the following Scale for one Adult).

Once aboard the social dynamics reflected a miniature republic with a disciplinary regime enforced by the captain, surgeon, matron for the single women and the men selected as constables to manage daily life. Several reports of the steerage experience use images of packed suburban slums and grimness with little sun, dampness, and a severe lack of privacy. Dickens, in his novel David Copperfield describes steerage as confined and gloomy, with berths, chests, bundles, barrels and miscellaneous baggage to add to the disorder.[10] The difficulties of getting a decent nights respite from the day are described as “By night the teeming married quarters must have blessed the screen of background groans from the ships timbers as they argued, wept, urinated, broke wind, copulated, snored, vomited, prayed, or cried out in dreams of the land they would never see”[11]

The Merchant Shipping Act of 1854 and Passengers Act of 1855 eventually set official standards on numbers, diet, procedures for cleaning, cooking and hygiene. Families with children over the age of twelve were split with the sons and daughters moving to the single compartments. The mix of nationalities and faiths caused some conflict on many a journey with Scots, Irish, English and Welsh crowded together in steerage with the commensurate prejudices and cultural misunderstanding’s that still plague the twenty first century. Groups were organised into messes, essentially a unit of domestic economy, to prepare food, eat and clean with their activities strictly timetabled. This included days for washing and collecting supplies, cooking, eating, collecting water, and inspections of both persons and accommodations. The mess captains were responsible for collecting breakfast and perishables from the issuing room daily and dry goods weekly. With the establishment of the depots, depots were established during their stay there. Religious services were part of the journey and generally held under the auspices of captain although ministers and lay preachers also held services to cater for the different religious beliefs on board.

Shanties for crew work routines{12] – Whiskey-o, Johny-o, Rise her up from down below,Whiskey, whiskey, whiskey-o, Up aloft this yard must go,John rise her up from down below.

Leaving depended on tides and winds. Sea shanties were often ‘the public announcement’ for emigrants that the anchor was been lifted and ship now underway. They were used to help crew coordinate their efforts thereby improving efficiency when pumping, hauling and working the capstan; essentially another hand on the rope. Shanties had a fixed chorus and a soloist who often improvised the content of his section. There were several types: short haul used when working on a halyard with efforts focused on a single word e.g. boots or aye; long haul to give a rest between efforts; vertical capstan shanties, the most musical and longest, as sailors walked in circles pushing the capstan bars in a long effort to raise the anchor; and pump shanties for emptying water from the bilge. These matched the tempo to difficulty with the shanty slowing at points in the song and then returning to tempo as needed. A ‘shantyman’ would led the crew in the call and response and chorus structure and would be a leader possessed of a strong voice and good memory.

Phase 2: Up to the end of the Sea-Sick Days

Richard Barton’s diary of 1839-40 provides a general sense of the experience and progress of those on board over their 138 days at sea. He first notes being invited to dine with New Zealand Company directors aboard the steamship Mercury on 14 September, by which time the Oriental, one of three ships carrying settlers, was already at Gravesend. He noted that the ‘Sutherland Highlanders dressed in uniform looked well and were much applauded.’ They wore new blue caps and jackets and tartan trousers. John Sutherland would have been attired in this garb as a Sutherland Highlander. All ships sailed the next day and the last of England was sighted on 28 September. The journey thus far had been plagued with heavy seas and strong winds. On 22 September the Superintendent Surgeon commented on wet and stormy conditions with the emigrants very sick. The Bay of Biscay was notorious for wild and heaving seas and would prove to be a troublesome experience for many emigrants and rarely escaped. Mal de mer resulted, according to diarist John Hillary[13], a ‘general rush for the buckets’ with ‘cries and groans from all sides…others lay still as death.’ Commonly, for those in steerage, a soaking from seawater breeching the hatchway would add to the misery. Several reports of a willingness to be tossed overboard point to the degree of misery for many. Those unaffected would spend their time dealing with those affected. Whether or not John and Mary Sutherland were spared this misery is unknown. A role constables, if they had their legs, would soon find themselves serving, was the carrying and emptying of slop pails for the afflicted as they clung to their respective abodes amid what can only be imagined a growing stench from the gastric offerings.

Phase 3: The Atlantic and heading south to the tropics

The Oriental’s first stop, on 16 October, was the Isle of Saint Lago’s capital Portopraia in what is now the Cape Verde Islands where the ship remained at anchor for three days. Barton was able to go ashore and records laying in ‘a large supply of excellent fruit’ during his visit[14]. The surgeon reports that he allowed emigrants to go ashore ‘in turns’ on both the seventeenth and eighteenth. They all returned in good time other than ‘two persons who returned rather late and in a state of intoxication, on inquiry I found that they drank but very little and that without eating anything all the day at their expressing deep regret…I pardoned them.’ The surgeon reports on 25 October that the weather was fine and emigrant births were all on deck, cleaned out and sprinkled with Chloride of Lime, a common disinfectant of the time. The minutiae of everyday was well established during this period with timetables and domestic chores structuring day and night. Flying fish, whales, porpoises, sunsets and moonlit seas where common images. This was a time for enthusiastic passengers to organise events to entertain and would prove to be the easiest part of the journey for all aboard.

The male adjustment to the in-between life as experienced in this period is reflected upon in a myriad of letters and diaries. It suggests a rearrangement in domestic affairs, particularly for married men in steerage, and single men. Perhaps the example of sailors blurred the lines during this period. Several reports from married men indicate care of both wives and children as they become rather more involved in domestic duties than usual. Reports of washing linens or taking over the hanging of wet items and taking responsibility for the children, cooking and washing dishes are not uncommon. Men have been recorded as building wooden furniture for their future homes and the surgeon reports four chairs being built for children attending the ship school.

Everyday activities were more difficult for all on board. An example is that of washing clothing and bedding. The provision of cold salt water on wash days would see a crowded deck of both women and men engaging in the activity. Difficulty in finding space in the rigging to dry clothing was a lament often heard. One of problems with salt water was the resulting dampness with the crystals absorbing the ready supply of moisture in the air. Sailors would overcome this by standing in rain to let fresh water wash the salt out, sometimes using soap on clothes still attached to their bodies much to the amusement of some passengers.

Phase 4: Becalming in the doldrums and the change of the constellations

For those of us born and raised in the southern hemisphere the Magellanic Clouds and Southern Cross are familiar, with the latter an integral part of the New Zealand flag. This was not the case for John and Mary. Looking at the night sky once reaching the line would have been unfamiliar. Barton reports variable winds holding up the journey ‘near the line’ for several weeks, although a distraction was a ship with emigrants for South Australia. The experience of being essentially stuck in the intertropical convergence zone is described by William Gray as ‘like being in a painted ship on a painted ocean[15].’ The experience was akin to residing in a sauna with high humidity and heat along with little sensation of movement, although the Guinea current ensured some progress. Shoes, stays and petticoats would have been untenable and the only sounds creaking yards and the occasional flap of a sail. Sunburn was another new experience for many with the resulting sting and rash. After discovering acquaintances on board the other unnamed ship, Barton was able to visit, a regular practice in the period and a good opportunity to send letters home. It is on his return that the mention of the Sutherland contingent is again mentioned. Barton writes “on returning late at night, Sandy and two or three more of the Highlanders came up and entreated me not to go in an open boat again.” Sandy was almost certainly Alexander Sutherland, the name he was known by, and it is certain the Sutherland families were close as already mentioned. This also highlights the value of the relationship the contingent had with Barton. The most difficult conditions for pregnant women were most likely around the storms and passing through the doldrums. By then Mary was at least eight weeks into her pregnancy and spending, what are often difficult months on the longest possible emigrant passage. All suffered from heat, humidity, loss of appetite, no breeze, and the impossibility of uninterrupted sleep. Men could repair to the deck at night, thereby escaping a cramped and uncomfortable environment. Tropical rainstorms made the suffering worse with steerage damper and stuffier with hatches closed to keep the rain out.

On 8 November, Barton records passing the line and mentions taking daily care of the needs and comforts of the Sutherland contingent. He notes that although his cabin was rather warm at 29.5 degrees Celsius other parts of the ship were significantly hotter. This would have pertained to steerage where both Sutherland wives were pregnant with Alexander’s wife close to seven months. Of his habits, Barton writes “read from six until breakfast (nine o’clock), then walk on the deck, and talk with all around, visit my own people, and attend to any request from them, return to my cabin and read until dinner, three o’clock. Rise from table about five. In good weather upon deck, otherwise to cabin; tea at seven, grog at nine; lights out at ten. On fine nights I generally stand hours afterwards on deck, beholding the cheerful space of the spangled heavens, conversing with those whose tastes lay the same way. Cards, chess, and backgammon was the amusement of many, but I never joined either.”

By 26 November the ship was by the Islands of Tristan D’Acunha off the tip of the coast of South Africa. It appears that the principal recreational activity was the shooting of albatross by passengers with one having a wingspan of ten feet (three metres). The island is how a wildlife reserve and weather station. By 1 December the surgeon was reporting ‘chest affections’ among passengers. The weather noticeably cooled the further south the ship sailed.

Phase 5 – South of Latitude 50 degrees and running the easting

Once past the tip of South Africa the Oriental would not sight land again until they reached New Zealand. It sailed on latitude 42 degrees south in the Southern Ocean. Barton mentions gales driving the vessel too far south to sight Van Diemans Land (now Tasmania). Undoubtedly, sleet, fog, heavy snow and icebergs where meet with some trepidation. Frequently, emigrants relate the effects of cold with chilblains and constant damp increasing discomfort. Seas have been described as ‘mountains high’ and during one storm, an emigrant on a later journey reports the experience as ‘like living in a square box in England with the door open and a strong wind driving sleet and rain in…no fire to compensate”[16]. Sea spray and the precipitous movements of the vessel where risky to those who ventured on deck with the risk of being swept off their feet by waves or washed overboard. Steerage passengers where often shut up below decks in the dark and called upon to bail as seawater transgressed their accommodations with bedding and personal items being set afloat reported on more than one vessel. Diaries are full of anecdotes of this phase of the journey. One writes that ‘Parnell went to galley to get scones…heavy sea soaked her but she saved the scones’ and tragically, that of a labourer’s child who was swept overboard and drowned[17].

A report in the journal of the surgeon located the Oriental at longitude 46.5 degrees on 14 December. Seas were rough with showers and emigrant Grace Spencer from Bradford gave birth to her first child, a son. Steerage was cleaned. On Thursday 2 January he writes that Heavy squalls saw…broke their lashings and ? along the quarter deck when coming in contact with some children, one of them Janey Johnson aged 10 years. She was the eldest of the five daughters of John and Ann Johnson. Both thigh bones were broken a little above the knee joints and she now lay in a very dangerous state; two other children were slightly bruised.

Barton mentions sighting a whaler at work which would not have been the most pleasant sight. His first sighting of New Zealand was Mount Taranaki ringed with its cloudy wreath, standing at 8261 feet (2518 metres); a mountain he had heard was 14000 feet (4267 metres).

Phase 6 – The Arrival

On 22 January 1840 the ship sailed into Port Hardy, a cove at D’Urville Island after sitting out to sea for the night due to heavy gales. The occupants of the ship had their first trading encounter with Maori, bartering for fish and potatoes. The next evening, after a day exploring on shore with other cabin passengers and ‘the gardener, Walker (one of my Sutherlanders)’ several of tribe arrived bringing pigs, fish, poultry, and vegetables. They sailed for Port Nicholson on the morning of 25 January 1840 with some difficulty due to south easterly winds beating directly against them and keeping them in the harbour for three days with the vessel lucky not to be wrecked on the Nelson Monument rocks. They eventually entered Port Nicholson in a strong north westerly wind with a pilot provided by Colonel Wakefield. The Oriental was anchored off Somes Island at 6pm on January 31, the second ship to arrive after the Cuba and Aurora who saluted their arrival[18]. This is subsequently the location of the birth of Alexander and Elizabeth Sutherland’s second daughter. Further diary entries regarding his men include noting that on 1 February he took eight ashore and allowed them to explore while he spent time with the gardener. On 4 February a large party landed to erect temporary dwelling with emigrants allotted 20/- per week as a wage. Barton initially settled with the Sutherland emigrants on the banks of the river above other groups.

Barton notes settling between two tribes who provided the group pigs and vegetables in exchange for clothing. He records an incident between a small group of the Sutherlanders’ with him and Maori. This resulted in his first meeting with the chief to resolve the issue which he describes as a korero. This was probably his first introduction to Maori tradition for resolving conflict. Barton describes an elderly member of the tribe explaining the slight shock of the recent earthquake as caused by “Atua” due to the fight. The exchanging of gifts took place with Barton receiving a dozen baskets of potatoes and a pig set aside to be fattened. Barton gave a bag of rice, sugar, and twelve yards of calico. Both agreed to banish the ringleaders of the incident.

| Name | DOB | Occupation | Marital Status | Last place of residence | |

| Anderson James and Ann | 1817 | Shepherd | Married | Brora, Sutherland | |

| Anderson David | 1819 | Shepherd | Single | Brora, Sutherland | |

| Anderson James | 1799 | Shepherd | Single | Brora, Sutherland | |

| Anderson John | 1815 | Ag Lab | Single | Brora, Sutherland | |

| Cormacher Peter | 1819 | Ag Lab | Single | Golspie Tower, Sutherland | |

| MacKay Alexander | (reported to be Elizabeth McKay’s brother) | 1813 | Ag Lab | Single | Brora, Sutherland |

| MacKay William | 1819 | Harness Maker | Single | Invergorden, Manis Ross & Cromarty | |

| McKenzie Thomas | (possible witness to registration of birth of John & Mary’s daughter Janet in 1842) | 1819 | Servant (possibly Richard Barton’s) | Single | |

| McLensan, Donald | 1820 | Ag Lab | Single | Brora, Sutherland | |

| Sutherland Alexander and Elizabeth McKay | 1810 | Shepherd | Married | Brora, Sutherland | |

| Sutherland John and Mary Gordon | (Barton is witness to registration of birth of daughter Elizabeth 1840) | 1816 | Ag Lab | Married | Brora, Sutherland |

| Tarvis Alexander | 1815 | Shepherd | Single | Aberdeen | |

| Walker John and Eliza | 1813 | Gardener | Married | Edinburgh |

Bibliography

[1] Professor James Hunter, October 2015 Sutherland clearances, extraordinary episode says historian in https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-34602284 accessed 19 November 2020

[2] Image in John o’ Groat Journal – Friday 19 July 1839

[3] Dr Evans in The Sun, London, Monday 16 September, 1839 Evening Edition. British newspaper Archives Accessed 18 November 2020

[4] Over the Mountains of the Sea Loc 102

[5] Fiona Kidman, Speaking with my grandmothers, in Where Your Left Hand Rests(Godwit, Random House, New Zealand) 2010

[6] Dr Fitzgerald, Surgeon-Superintendent. Medical Journal, Oriental, 1839

[7] The Isle of Dogs, London Extracted from The Pocket Atlas and Guide to London, 1899. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Isle_of_dogs_1899.jpgAccessed 2 November. 2020

[8] James Goss, 1858 in Fraser, L, Szczepanski, J and Rosevear, E (2019) in The sea was going mountains high” Shipboard accounts at Canterbury Museum. In Records of the Canterbury Museum. Vol 33: 31-77

[9] Hastings, David, 2012. Over the Mountains of the Sea: Life on the Migrant Ships, 1870-1885. Auckland: Auckland University Press (Loc 189)

[10] https://www.gutenberg.org/files/766/766-h/766-h.htm#link2HCH0057

[11] On steerage – Hazelwood, Don (2018) The Long Farewell: A history of the first migrations to Australia. Lume Books p 107

[12] Risko, Sharon Marie, “19th Century Sea Shanties: from the Capstan to the Classroom” (2015). ETD Archive. 658.

[13] Hastings, David, 2012. Over the Mountains of the Sea: Life on the Migrant Ships, 1870-1885. Auckland: Auckland University Press (Loc 626)

[14] Diary entries of Richard Barton 1830-40 in Letters by the Husband of Hannah Butler 1840-41 In Earliest New Zealand by R. Barton. Masterton: Palamontain and Petherick, 1927.

[15] Hastings, David, 2012. Over the Mountains of the Sea: Life on the Migrant Ships, 1870-1885. Auckland: Auckland University Press (Loc 817)

[16] James Worsley in Hastings, David, 2012. Over the Mountains of the Sea: Life on the Migrant Ships, 1870-1885. Auckland: Auckland University Press (Loc 964)

[17] Ibid (Loc 982)

[18] In Henry Brett, White Wings, Volume II, 1928. Auckland: The Brett Printing Company.