A change in tradition in relation to cleaning occurred in the early eighteenth century as “…householder[s] in England…transform[ed] small children into human brooms for sweeping out their flues”[1]

In April 1880 the Sligo Workhouse master informed his governors that the chimneys needed sweeping. However, the contractor had died recently and he did not feel it prudent to bring in the son in his stead. How was he to progress? The governors ordered the purchase of a chimney-sweeping machine to be operated by resident paupers.[2] The contract had only just been renewed at £10 (around £1263 in 2021) per annum. The master sweep, my three times great grandfather, William Anderson, had held it for at least the past thirty years. He died on 12 March at the age of 62 years of typhus fever, the day before the renewal of the contract was confirmed on 13 March 1880[3].

The first mention of William is his marriage to Margaret Hill, witnessed by Mark Smyth and Cecelia McHugh, in the Roman Catholic Chapel on 4 January 1841 in Sligo. How he became a master sweep, his attitude toward the use of children as apprentices and the use of new technology can only be speculated. Some master sweeps were apprenticed as climbing boys, some were never apprenticed to the trade. Some purchased an existing business, inherited their father’s, married a sweep’s widow, or simply needed an income. What is known is that William had apprentices, employed journeymen and owned at least two sweeping machines during his career. His youngest son, named William, also entered the profession for a time at least.

Increasing numbers of sweeps through the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century are attributed to urbanisation and the construction of brick, multi-storied homes that included numbers of chimneys in the ‘Italian fashion’. Using numbers of climbing boys reported in London in 1801, with a population of about one million, Kelly compared Ireland’s largest city, Dublin, with a population of about two hundred thousand, to estimate it would have required eighty to ninety climbing boys to keep Dublin’s chimneys from becoming a fire risk in the early nineteenth century.[5] In 1800, Sligo town’s population was only ten thousand souls so would have required around four.

Sweeps kept flues clean, helped prevent fires, were early firefighters and in the summer months would often be the nightmen (emptying the night soil) to keep income rolling in. They also sold collected soot to farmers, dealers and locals for fertiliser. Larger houses were usually swept once every three months and could yield around six bushels of soot per annum. With around 350 master sweeps in London in 1851 this amounted to at least one million bushels that were sold in Hertfordshire, Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridge, Essex and Kent.[6]

Early methods for cleaning where through the use of long handled brooms of birch twigs, bundles of straw or holly bushes and, noted in Ireland, geese or turkeys. The bird was dropped down the chimney then pull up be a rope around their necks. Their wings as they flapped would do the job. Sometimes fires would be deliberately set alight to loosen crusts of soot. The introduction of coal increased the risk of residue forming as fumes thickened and congealed. The resulting ash, soot and creosote needed to be scrapped and brushed off.[7]

Apprenticeship and the use of Climbing Boys and Girls

Apprenticeship in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was usually about one party teaching and one party learning. Tradesmen or artisan parents wished for their children to learn a trade or craft. The role of the master sweep was to provide food, clothes, shelter, a bath once a week and access to church. Apprentices, committed to indentured servitude for seven years, were to obey, not waste resources, lend gear or sell secrets. Journeymen were usually out of an apprenticeship and managed apprentices for master sweeps. Often apprentices were orphans or foundlings from the workhouse or sold by their parents to a master sweep.

Children who were young, small and thin were preferred, all the better to negotiate tall, convoluted chimney systems and the increased number of narrow flues, some less than fourteen inches square. This was in part due to the hearth tax on the number of chimneys that was introduced in the 1600s. Builders needed to economise on space and build to fit around living areas. Flues prevented heat escaping and shut out drafts. For the young sweep, climbing and cleaning was done in conditions that were pitch black, claustrophobic, suffocating, hot and difficult to navigate.

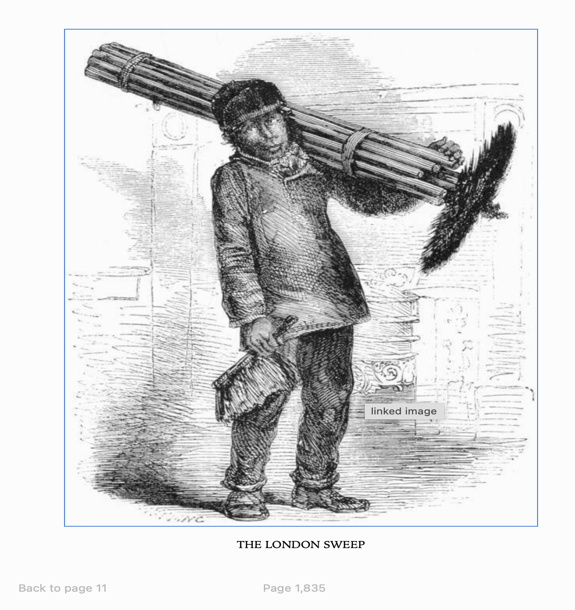

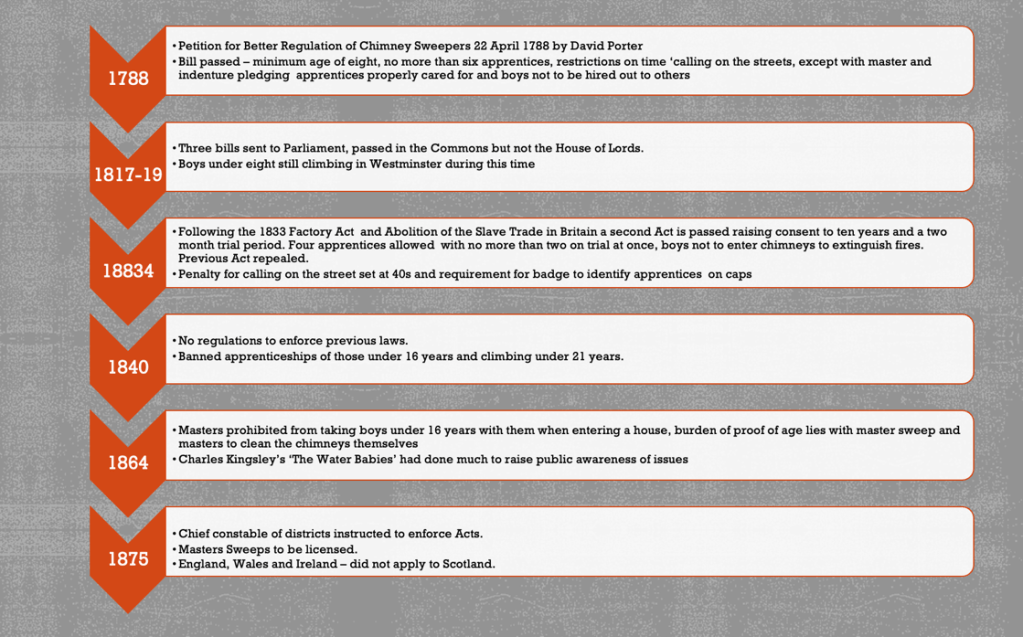

It is not known when children first become climbing boys. They worked with bare hands and feet, often naked, and with no rope. Their tools were a scraper and brush, and work started well before dawn. Jonas Hanway (1712-1786), philanthropist and founder of the Magdalene Hospital, brought a bill to Parliament in 1788 proposing better protection of children in the trade. He believed master sweeps should be licensed and apprentices registered by name and age. The bill was rejected, but a Chimney Sweeping Act legislated that no master was to have more than six apprentices and none were to be under the age of eight years. This was not adhered to and inquiry into ages beyond statements of parents or the master in orphanages was not common. The Newgate Calendar records prosecutions for cruelty, however, interpretations of what that meant were not always agreed upon.[10]

“Climbing-boys, shouting their shrill cry of “all up” from the chimney-tops, were heard more and more frequently throughout eighteenth-century England as the demand for their services, resulting from narrow flues and coal fires, constantly increased. As an institution, the climbing-boys became a sociological and economic problem…the hardships of their trade [were] so horrible that Parliament was forced to enact various regulatory measures”[11]

Lack of regulation and too many sweeps vying for work meant prices were being driven down and too many children taken on and neglected. Many sweeps struggled to earn enough to support their families, journeymen and apprentices. Ethical issues around the use of climbing boys was increasingly noted by wider society as incidences were reported of young children maimed, diseased, deformed, lacerated, ulcerated, murdered and out in all weathers.

The first disease attributed to a specific occupation was scrotal (testicular) cancer in chimney sweeps. Reported by Sir Percival Pott in 1775, he believed it was possible to save the life of the sufferer if found early enough. Self-treatment in the sweeping fraternity was to pinch the affected part of the scrotum between two sticks and scrape the cancer off before it spread too far.

Reformers

Notable reformers in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries included David Porter who was trained by his father in Peterborough and established a successful business as sweep, smoke jack cleaner and soot trader in London in the 1770s. He published a tract in 1792 called ‘Considerations on the Present State of Chimney Sweepers’ listing thirty proposals for the care of apprentices, set up friendly societies, assisted in the transformation of his friend Hanway’s proposals into legislation, and wrote statutes for fraternities. He was not against the use of climbing boys and argued against their abolition. Porter became a builder and property developer in 1803 and built Montagu Square in London with many place names in Marlebone associated with him.

“No one knows the cruelty which a boy has to undergo in learning. The flesh must be hardened. This is done by rubbing it chiefly on the elbows and knees with the strongest brine, close by a hot fire. You must stand over them with a cane, or coax them with the promise of a halfpenny, et., if they will stand a few more rubs.”[12]

Lord Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley-Cooper (1801-1885), led a campaign to end the practice of climbing boys in the nineteenth century as part of his concerns about ‘the abuse of children in manufactories’. He proposed the Chimney Sweeps Regulations Act of 1864 that contained penalties for employing children but this was another that was not fully enforced. He was finally successful in 1875 with the Chimney Sweepers Act that meant master sweeps had to be registered with police and supervised. This allowed the industry to adopt more traditional equipment and techniques to clean chimneys.

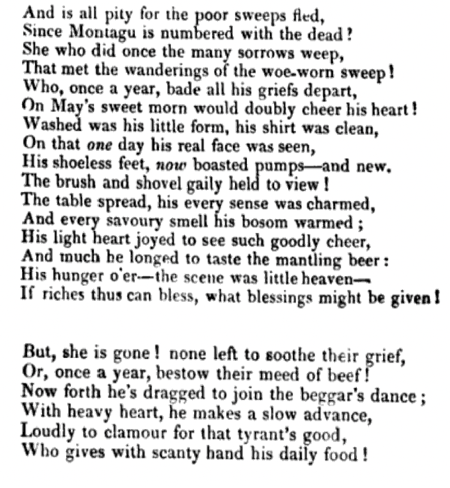

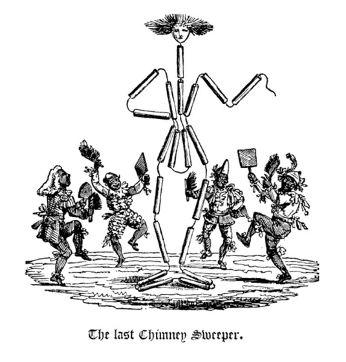

Lady Elizabeth Montagu (1718-1800) held a May day feast at Montagu House in London for climbing boys. The children were given a shilling and fed on roast beef and plum pudding. She was a philanthropist and founding member of The Bluestockings Society, a women’s literary discussion group. There are many rumours around her interest in climbing boys, particularly relating to her son being stolen, becoming a climbing boy and finally restored to his mother. Although she did have a son, he died a year after his birth. She knew Porter and had attended his meeting of the “Friendly Society’ at his home in the year of her death.

Technology

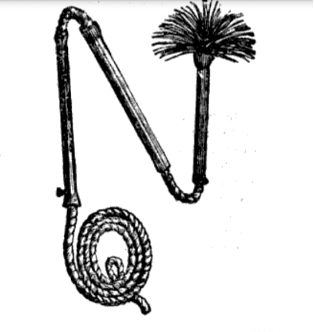

Machines for cleaning chimneys were available from end of eighteenth century but not in general use until 1875. They were controversial for a range of reasons. One was the difficulty before 1852 in obtaining a patent. Registration of an invention was tedious, costly and an applicant needed to be literate. The process was simplified after 1852 so an applicant only needed to apply to one office as opposed to up to seven. The first machine, essentially an elastic brush, was registered on 28 May 1789 by John Elin. Another was patented in 1796, the same year the ‘Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce’ launched a competition for the invention of a simple and affordable machine. First prize was a gold medal or 40 guineas (around £1950 in 2017).

It was not until the founding of the ‘London Society for Abolishing the Common Method of Sweeping Chimneys’ (SSNCB) in 1803, uniting both in a common cause, that the medal was finally awarded to George Smart. A carpenter, he had seen children inserting string into tobacco pipes to make a rod. In 1803 created a machine with his foreman, also sweeping his own chimneys. Although initially denied the prize, with further modifications, including a brush which opened and shut like an umbrella, and letters from householders, he was finally awarded the prize in 1805. Smart was again awarded the prize in 1807 for his ‘Scandiscope’. The cost of the machine, with an extra brush and extension of rods up to 60 feet, was £4 14s 6d (approximately £220 in 2017). Brushes lasted around two years.[13]

Another developer, Bristol engineer Joseph Glass (1791-1867), launched a machine made of solid cane with brass screw joints, extendable rods and brushes in 1828. It was strong and pliable with a wheel at the top of the brush-head to make it easier to push up the flue. Both machines included cloths to catch the soot though which the machine could be worked.

Acceptance of Technology

Many master sweeps, architects and insurance companies supported the use of machines, Several, however, were not easily convinced. Neither were many home owners. Concerns were based around expense, efficiency and fear of change with common argument including; horizontal flues and internal ledges requiring the use of climbing boys, men needing to work machines resulting in higher wages, and machines needed maintaining. For the sweep perquisites (essentially kickbacks like pennies or pies) were not given to machines, and with only fifty or so in use in 1817, it was argued this was only in the homes of those who were ‘authoritative’ over their servants who were receiving kickbacks by the use of boys.[16] Machines also opened the doors for inexperienced men to take up the trade.

Back to William Anderson

A case at the Borough Petty Sessions in 1867 saw William charge sweep Peter Owens with stealing part of his sweeping machine. Owens charged William with the same offence. A number of thick poles with screws attached were produced in court. William claimed he had obtained the machine from London around 1860 and parts had gone missing three or so months ago. It was common for Owens to borrow the machine as William hired him for jobs, paying him half the profits. This case was withdrawn but another was brought forward relating to six joints belonging to a second machine owned by William who stated it had been given to him by Collins, another sweep, previously employed by him, and lately gone to England. The joints had been found in his house after a police search, with Owens claiming ownership saying he had gone to the house tipsy and William’s daughter Mary Ann had taken them from under his arm. A scuffle broke out between the parties, resulting in the arrest of William, who nonetheless also won this case, and was released after being fined 2s 6d and costs. It is interesting to note that the joints were made in Sligo from the same mould for sweeps Owens, Kelly and Collins.[17]So we know that William used machines from at least 1860, most likely earlier. With a record of an apprentice sweep, 10 year old, Thomas Brennan appearing in a prison record for assault and breaking and entering with William’s son Richard in 1871, and entered as living with the Anderson’s, we also know he was employing children under the age of sixteen.

[1] The Abolition of Climbing Boys George L Philips in The American Journal of Economic and Sociology Vol 9 No 4 (July 1950) pp. 445-462

[2] Sligo Independent, 10 April 1880

[3] Sligo Independent, 13 March 1880

[4] London Labour and the London Poor Vol 2 1851 Henry Mayhew Gutenberg Press

[5] Chimney sweeps, climbing boys and child employment in Ireland, 1775-1875 by James Kelly in Irish Economic and Social History, 2020, Vol 47 (1) pp. 36-58 page 40. Estimates in London where 500 climbing boys, 200 master sweeps and 170 journeyman.

[6] London Labour and the London Poor Vol 2 1851 Henry Mayhew Gutenberg Press

[7] British Chimney Sweeps: Five Centuries of Chimney Sweeping by Benita Cullingford 2000 Great Britain: The Book Guild, Limited.

[8] http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/acts/index.html accessed 21 November 2021

[9] Photograph Denise Brown

[10] London Labour and the London Poor Vol 2 1851 Henry Mayhew Gutenberg Press

[11] George l. Phillips, England’s Climbing-Boys: A History of the Long Struggle to Abolish Child Labor in Chimney Sweeping (Cambridge MA:

Harvard University Printing Office, 1949), p 1

[12] Quote by Mr Ruff, Nottingham, Master Sweep p 245 in The Murder Of Innocents in The British Medical Journal, Vol. 2, No. 139 (Aug. 29, 1863), pp. 243-245 Published by: BMJ

[13] British Chimney Sweeps: Five Centuries of Chimney Sweeping by Benita Cullingford 2000 Great Britain: The Book Guild, Limited.

[14] The Every-Day Book and Table Book or Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Sports, Pastimes, Ceremonies, Manners, Customs, and Events, Incident to Each of the Three Hundred and Sixty-five Days in Past and Present Times… By William Horn London: Printed for Thomas Tegg and Son 1837 accessed 16 November 2021 on gutenberg.org

[15] London Labour and the London Poor Vol 2 1851 Henry Mayhew Gutenberg Press

[16] London Labour and the London Poor Vol 2 1851 Henry Mayhew Gutenberg Press

[17] The Sligo Independent on Saturday April 13, 1867