Finding your way: Life in 19th Century Garioch

“Language is built on not only what is spoken but what is unspoken; the richness of the social structure…[and] other aspects form the words we speak and…how they are communicated” (Dame Evelyn Glennie (2019)[1]

In his book Thirty-Two Words for Field: Lost Words of the Irish Landscape Manchán Magan identifies 70 000 place names, over 4,300 words used to describe character and twenty one for holes. Living in Ireland and having Irish speaking friends has introduced me to the way that layers of knowing and understanding are made explicit through language.[2]

Helen Beaton’s (1847-1928) book ‘At The Back o’ Benachie (or Life in the Garioch in the Nineteenth Century)’, published in 1915, is a rich rendering of nineteenth century Garioch rural life and language. It is here, in the north east of Scotland that my 3x great grandparents Ann and her husband Robert lived, farmed and raised a family. (They are the grandparents of my great grandmother, Annie Webster of the last post). In this rural community social bonds were entwined through every aspect of local life. Shared language developed community cohesiveness and identity and rituals provided structure and a way to navigate life events by providing a ‘communally wise path’ and a way for emotion to be ‘contained and channelled’[3].

North East Scots or Doric has the most ‘maximally north-east features’ in the area of Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire up to the west of Inverurie.[4] Ann would have spoken and understood life and death through Doric. It is probable her experiences of courting, marriage, birth and death also mirror Beaton’s memories.

‘Scots’ is the native Germanic vernacular, descended from Northumbrian dialects brought in between the seventh and twelfth centuries of non-Gaelic Scotland. Broad Scots differs in sounds, structures and words; and also between fishing and farming communities within the same geographical area. Doric is known as such due to its association with the farming community.

Distinctive features of local Doric:

- Use of ‘fih’ in place of ‘wh’, for example, ‘fit’ for ‘what’

- Words local to the area, for example, cappie (ice-cream), stewie-bap (floury roll), and ficher (play with your fingers).

- Moon becomes mean, school becomes squeal, stone becomes steen[1].

Mrs Ann Smith wis baptised Ann Murison, it Bartholchapel on twinty July 1822. She wis the dother (daughter) o George Murison, a dominie (teacher) an his dame (wife) Barbara Scorgie. Ann merriet (married) Robert Smith on 27 May 1846 at the Chapel of Garioch and they hid fower bairnies (four children), three loons (boys) namyt William, Robert and Peter and a quine (girl) namyt Ann. They bed ootbye (lived out by) Bourtie it Old Meldrum. Robert deid in 1864 and wis beeriet (was buried) in Bourtie Kirkyard, along wit loons William who drooned (drowned) in 1871, aged 24 and Peter deid of peritonitis in 1874 aged 19.

Ann Murison exhibited significant resilience in her roles as wife, mother and grandmother. Care was ‘deep and rooted’[5] in rural areas and it is likely this, along with a strong sense of place in her community, helped Ann in her role as a stabilising influence for her family. From 1864 on until her death 36 years later in 1900 she faced the premature loss of children and husband, maintained then moved off the farm she had shared with her husband and cared for daughter Ann’s four illegitimate children. How much of these cultural influences, beliefs and practices did she pass to her daughter Ann and granddaughters Annie and Lizzie? And how much of them did my great-great grandmother Annie Webster keep close and incorporate into her own life?

Beaton on courting and marriage, birth and death

Courting and marriage

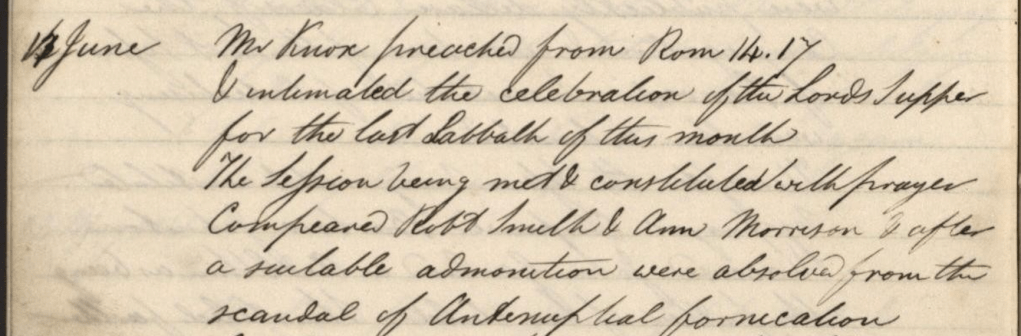

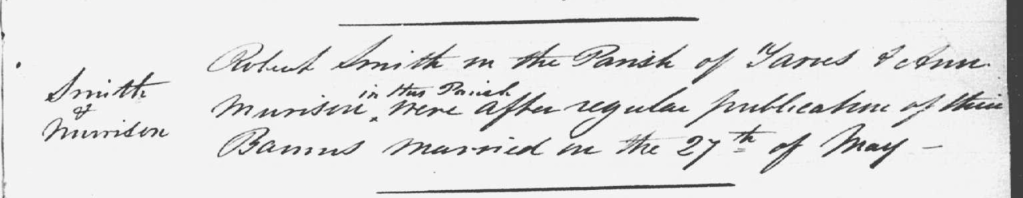

Girls in the Garioch where described as ‘coy and long in leaving their girlhood’. They often engaged in clandestine courting and trysts with Valentines and secret messages and signs often saying ‘luik as if ye werna luikin’ tae me’ (look as if you weren’t looking for me). Affection was ‘deeply rooted’ and parents would keep a girl in solitary confinement until she ‘wid come tull hersel’ when she would not give up a lover’[6]. Did Ann understand her own daughter Ann’s relationships and pregnancies through this lens? She was most definitely pregnant herself when she married Robert. The couple were compeared “and after a suitable admonition were absolved from the scandal of antenuptial fornication” on 14 June 1846 at the Tarves Kirk Session.[7] By this time they were married but unable to escape the kirk’s oversight.

The couple married 27 May 1846 at the Chapel of Garioch and son William was born 22 October 1846, just under five months later. He was baptised on 2 November in Tarves where both Robert and Ann were originally from in front of witnesses James Milne and William Smith who is possibly Robert’s father. Tarves is thirteen or so miles east of Garioch and I suspect Ann had gone home to give birth to her first born, William. Son Robert, born 25 February 1850 was also baptised in Tarves on 11 March 1850 in front of witnesses Peter Smith, probably the brother of Robert and better known as Patrick and George Dugan. The couple’s third child Peter (Patrick) would be baptised close to home in Bourtie.

Impending marriages were ‘cried’ at the commencement of three church services. Brides were expected to spin their own bed and table linen, underclothing and a wedding shirt for the intended groom. On the evening before the wedding the feet of groom and bride were washed by their respective friends. The grooms would often be blackened and the brides dunked with her shoes as she tried to escape. Grooms walked to the church with their party, and the bride with hers. Guns were carried and used at intervals to drive away evil spirits[9], as well as sweets for passing children and women and whisky for passing men. At farms, all were asked to drink to the couple’s health and after the ceremony the groups would join and head to the brides home. People met on the way were obliged to walk a few paces with the company.

On farms, barns would be cleaned and tables placed in the middle. Seats were constructed of planks of wood resting on bushels of oats or barley. The feast usually comprised large portions of beef boiled or roasted in large pots or ovens hung over a fire of sticks and peat. Peat was piled onto the top of the oven lid and puddings fired under sheets of iron. Milk puddings with currants and fowls (sent to the bride in large numbers) were common. Bowls of strong toddy often saw the male guests under the table. On entering their home a bannock would be broken over the bride’s head, along with a kebbuck (cheese) to symbolise good luck and plenty. The couple were then ‘bedded’, that is, put into a box bed in their wedding attire and locked in[10].

Birth

It was not unusual for women to go ‘home’ to their parents for the birth of their first child. Birthing was the domain of women; ‘those who were strong lived, and the weak mostly died’. Fivert (fevered) mothers had a cloot (cloth) wrung out of cold water and put on her forehead[11]. On the arrival of the baby ‘superstitious freets (beliefs) had to be seen to’. The women present all pronounced an opinion on the ‘puir little ablich’ (poor little small person) or ‘suncy weel faurt geet’ (…well looking child)’. Critically, what you did or did not do determined the infant’s health. If a child had black spots (moles), good or evil was predicted based on their position and a child born with a seelie-hoo (caul) was lucky in that they would ‘nedder droon (drown) nor wint (want).’

The whole community would visit and partake in the ‘cryin kebbock’ (a kneevlick o’ cheese an’ bread and home-made whisky or ale). Women would gift a ‘hansel tae th’ bairn’, usually in the form of a bottle of whisky, cheese or a few penny biscuits (as large as a cheese plate and pierced with holes). By the middle of century it was becoming common to baptise the child in the home instead of the church. Neighbours, relatives and the priest would attend. Men would dress in ‘knee breeches, blue-tail coat and brade bonnet’ with women in their best goon, red duffel coat and gippy-mutch (cap with heater shaped crown). If the infant did not have a brooch pin in its barrie to keep off the witches, one may be loaned or gifted.

Death

Omens predicted death or trouble. Dogs howling for several nights or a cock crowing after daylight meant ‘somebody bidin’ there is gaunn tae dee.’ Much like the banshee in Irish folklore. If a person did or failed to do a certain thing he was said to be ‘fey’ (he would die or trouble would come to him). Strange noises or the appearance of particular animals could mean evil in some form. While a corpse lay in the house, the 8 day clock (only requires winding once a week as opposed to daily) was stopped, furniture and pictures were covered with white sheets and tablecloths, and cats were fastened up to ‘stop the next person it met going blind’. Coffins were normally of white wood painted black outside. Neighbours invited folk to the burial. If on a farm, the barn was cleared and seats provided. Whisky and wine would be handed out and the minister held the service. A mort cloth covered the coffin and it was carried to the churchyard by family and friends relieving each other at intervals.

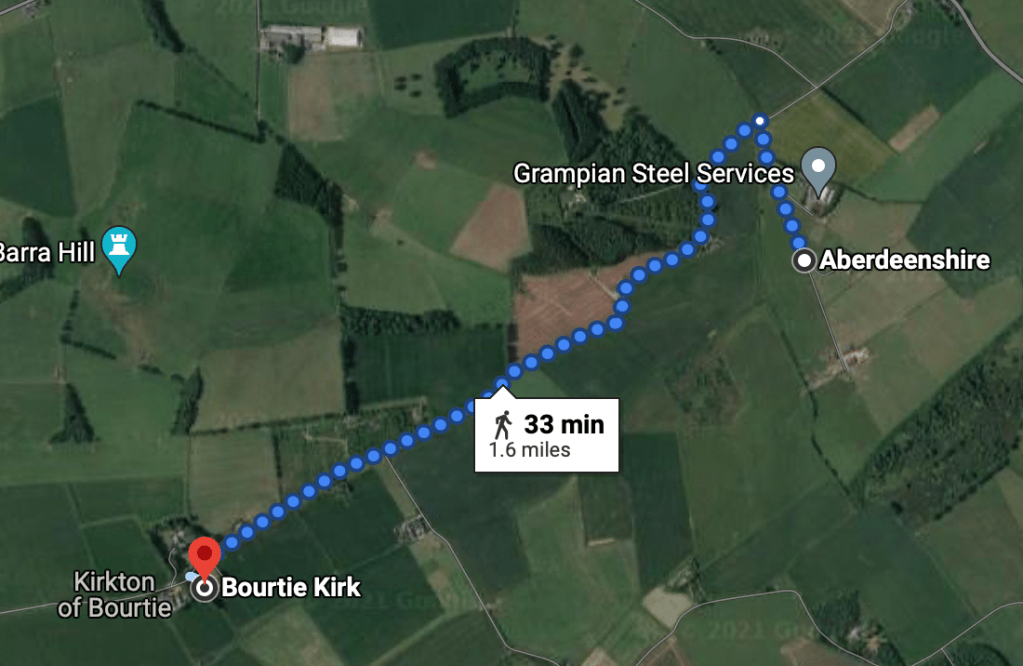

Husband Robert and sons William and Peter are buried in the Bourtie Kirkyard, a walk of 1.6 miles from the farm of Greenfields in Bourtie. Family and friends would have carried the coffin down roads and past fields that had occupied much of Roberts adult life, climbing around 160 feet as they did. I have found no evidence as yet of the hire of a mort cloth, a black and usually velvet piece of cloth for Robert but it likely that one was hired. They were hired from the kirk sessions who would usually use the fee for poor relief. Kirks often had a range, smaller ones for children and more elaborate ones for those who could afford them. Some trades had their own for members.

An inscriptions reads: Buried in Bourtie Kirkyard. Inscription is as follows: In memory of Robert Smith, farmer, Greenfield, Bourtie d. 24 July 1864 age 50. His son William aged 24 and his son Peter d. 12 April 1874 aged 19. Erected by his widow and family.[13]

[1] Dame Evelyn Glennie for Jill Cantlay McWilliam (Doric Future and Doric TV), 2019

[2] https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/thirty-two-words-for-field-50-for-penis-what-the-irish-language-tells-us-about-who-we-are-1.4334904by Jennifer O’Connell 29 August 2020

[3] Ochs (2017) https://news.virginia.edu/content/evolution-modern-rituals-4-hallmarks-todays-rituals

[4] Professor Robert Millar, University of Aberdeen in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oH8pxfqgSBQ – The Elphinstone Institute

[5] Cameron, D.K. (2008). Willie Gavin, Crofter Man. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited.

[6] https://www.thedoric.scot/helen-beaton.html#

[7] Tarves Kirk Session Minutes 1841-1855. CH2/511/1. National Records Office of Scotland

[8] Old Parish Registers Marriage 179/20287/ Chapel of Garioch page 287. National Records of Scotland. Accessed 11 May 2019

[9] http://www.nefa.net/archive/peopleandlife/customs/folk.htm

[10] https://www.thedoric.scot/helen-beaton.html#

[11] ibid

[12] Bourtie Kirk cc-by-sa/2.0 – © David Robinson – geograph.org.uk/p/5919289 accessed 7 November 2021

[13] ‘Kirkyard of Bourtie (and Oldmeldrum Episcopal)’ ISBN: 978-0-947659-85-1 Transcribed by Aberdeen & North-East Scotland Family History Society